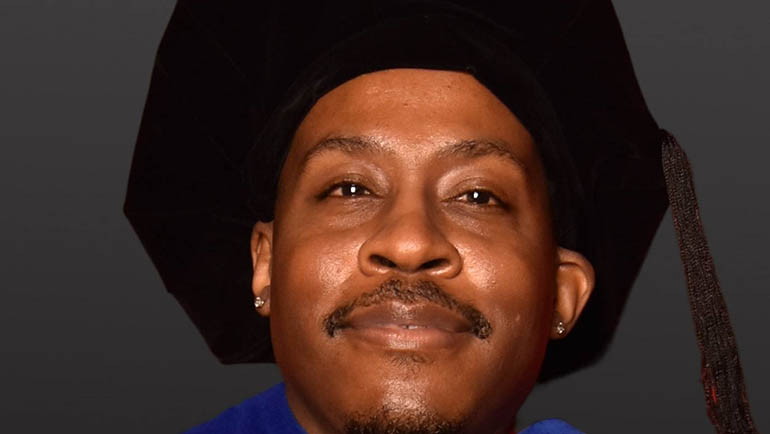

As a child growing up with “unconditional love of and for Blackness” inside the iconic Shrine of the Black Madonna church in Detroit, Wayne State University postdoctoral fellow and researcher Bakari Wallace, Ph.D., says that, when he grew older and ventured further into the world, he was stunned to realize how deeply racist stereotypes of Black men — and Black fathers in particular — dominated the misperceptions of so many.

“In the Shrine, I felt safe, I felt protected, I felt unconditionally loved,” Wallace said. “It was like this utopia-type experience, at least for me. And we weren’t really prepared for life outside the Shrine. You come to the realization oftentimes that everybody doesn’t have that love, not even your own.”

Wallace heard it all over the years, about how Black dads were too often absent or uncaring or deadbeats. But a lifetime steeped in the pro-Black theology of the Shrine had taught him to know better, to reject such blanket mischaracterizations. And over the past several years, the researcher has devoted his work to exploding myths about Black dads.

Such resistance sits squarely at the center of Wallace’s postdoctoral research project at WSU, a yearslong study of how negative attitudes about Black men impact the involvement, roles and perceptions of Black fathers in the academic lives of their children. Assembled with his mentor David J. Pate, Wallace’s study, “They Care About Their Kids: Black Fathers and the Reproduction of Anti-Black Misandry,” draws from two years’ worth of interviews with 30 Black fathers from throughout the country about their experiences dealing with schoolteachers, counselors, administrators and others while trying to cultivate their children’s academic growth.

As WSU continues to expand its commitment to community health and empowerment, studies such as Wallace’s are critical to understanding crucial segments of underserved communities.

“In talking with them, I started to identify that their experiences were, in many ways, an extension of what’s happening to Black men in society, broadly speaking,” said Wallace. “We often think of Black men’s experiences — particularly poor Black men — with the police, in the community, in the employment sector. They talked about their experiences in their children’s schools, how they were treated, how they perceived they were seen in these spaces, and it matched how Black men are generally seen throughout society.”

Wallace noted that many of his study subjects felt unwelcomed in schools, others overlooked or dismissed.

“It went to the established notion that Black men are criminalized just by virtue of our bodies and how we walked through space itself,” he said. “One Black father, for example, talked about how he would either drop off or pick up his child at preschool and how they would treat him suspiciously, follow him while he’s in preschool without necessarily engaging who he is. They didn’t talk to him. Other fathers would talk about how their interactions with the teachers were brief, very short. They would oftentimes be with their partner, and the school personnel, —primarily teachers — would not address them, would not talk to them. They often invoked this idea of the missing Black father trope: ‘They didn’t think I was around anyway, so they never reached out to me, never talked to me.’ The criminalization of these men, which matches how we’re often seen in society, was also a case in the school.”

At the other end of the spectrum, Wallace discovered, some fathers felt as though they were being unduly praised just for showing natural concern for their children’s education.

“There was as the additional experience of ‘exceptionalizing,’ which was an interesting take,” he said. “And the fathers were aware of it, how some were treating them as if they were the exception to the rule. People would say things like, ‘Oh, you speak so well,’ or ‘I wish more of you would show up.’ They’d hear very patronizing, backhanded compliments, which also is a demonstration of how larger society thinks of Black men and Black fathers specifically.”

Wallace, who earned his bachelor’s from Wayne State and spent many years organizing in Detroit as part of the group Helping Operations for People Empowerment (HOPE), began the study about seven years ago, after another mentor approached him with the idea while he was pursuing his Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin.

“She said, I’m interested in how Black fathers conceptualize their role in the academic socialization of their children. She told me she’d pay me to help me, so I was like, as the youth would say, ‘Say less,’” Wallace said. “I hit the ground running using some community organizing techniques I learned. I went where Black men are — barbershops, fatherhood programs. I found key folks in the community who could connect you to Black fathers. You speak to this father in their home. You speak to that father in the library. You might speak to another father in a fast-food restaurant.”

Asked whether his passion for the research reflected and extended the lessons he was taught about the beauty, value and humanity of Black people as child in the Shrine of the Black Madonna, Wallace didn’t hesitate in his reply.

“A hundred percent,” he said. “I identify as a Black studies scholar grounded in the Black radical tradition. I know of no better example than what I grew up in as a material instance of the Black radical tradition. It wasn’t just Black radical thought; it was Black radical thought put into practice. And so that absolutely shaped my framework, my thinking around anti-Blackness, not even 100%, but 1,000%. It’s an inextricable connection.”

Wallace observed that the project yielded an abundance of information that went far beyond the fathers’ relationships to the school system.

“Even though we were interested in the role that they played in the academic socialization of their children, the project itself allowed for us to ask deeper questions,” he said. “And in a way, we got into their life story and what were their own experiences in schools, and how their experiences connected to what they do with their children as it relates to schools.”

When he enrolled in Wayne State’s Pathway to Faculty program, which prepares participants for jobs as university faculty members, Wallace brought the project with him so he could continue to analyze the study. As his studies wrap up, he’s considering practical applications for his work.

“The goal, as far as the findings are concerned, is to expose the findings, the study, have these conversations and distribute the findings to multiple audiences,” he said. “I'll just be transparent here: I don’t do it with the intent of somehow ending what happens to Black men, and in this case Black fathers. I don’t know if we can end it. That isn’t to suggest that we shouldn’t do anything about it, though. So what I aim to do is to push forward conversations that might contribute to action plans around creating spaces for Black fathers in these schools, contributing to designing creative programs that fit the moment in terms of engaging Black fathers.”

Amanda Bryant-Friedrich, Ph.D., the Dean of the WSU Graduate School, hailed both the Pathway to Faculty program and Wallace’s work.

“Our Pathway to Faculty program reflects WSU’s commitment to continuing to build a diverse professoriate devoted to uplifting and strengthening the community around us,” Dean Bryant-Friedrich said. “Additionally, research such as Bakari Wallace’s, which aims to empower Black fathers as vital and respected participants in the academic lives of their children, not only underscores the importance of building faculty diversity but also illustrates the significance of our work in driving the upward social mobility of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged segments of our society.”

When weighing how his work might be used, Wallace said he encourages non-traditional approaches to embracing Black dads in schools.

“It doesn’t necessarily have to align with traditional modes of participating in your child’s school, such as going to parent-teacher conferences or parent-teacher associations,” he said. “You can do virtual programs. You can ask the fathers to read to kids online in addition to coming into the school.

“Ultimately,” he continued, “the aim is to let folks know that what happens to Black men, what happens to Black fathers throughout society, also happens within these schools, in these spaces that aren’t often thought about. That’s number one. Number two, it’s to demonstrate to our own community that we tend to fall into the habit of thinking that Black fathers aren’t there. They’re very much there and take an active role in their families and their communities’ lives.”