Emeline King leans forward and closes her eyes briefly, fanning her hands under her nose as if inhaling the aroma of a steaming pot of gumbo. In this instant, she’s 11 years old again, strolling with her father through the Design Center of Ford Motor Co. during the company Christmas party, olfactory senses tantalized by a strange scent wafting from behind a nearby set of huge blue doors.

“It was the clay,” recalls King, identifying the scent. “My father would take me to special areas around the building, and one area was near where they worked on the clay models for their cars. I had dabbled in clay before, but I had never smelled anything like this. I was fascinated over the smell of this clay. I wanted to get behind those blue doors.”

But those blue doors didn’t open for everyone, she learned: “My father told me, ‘Behind those doors are men who design cars. And you would have to be a transportation designer and a Ford employee. You have to work here to be a part of this clay.’”

In that moment, King says, her future was set.

“From that day forward, I made a promise,” she says. “I said three things I wanted to do: I wanted to become a transportation designer designing cars. I wanted to work for Ford Motor Company. And I wanted to work there with my father designing cars.”

More than a decade later, she made good on that promise. And she didn’t just pass through those doors either. Emeline King broke them down.

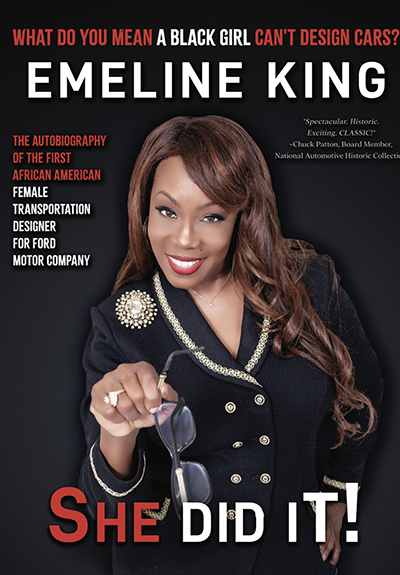

After earning her bachelor’s degree in industrial design from Wayne State University, King would eventually spend 25 years at Ford, becoming the first (and, as far as she knows, only) Black woman to work as a transportation designer at the auto manufacturer. Over that quarter century, she played key roles in some of Ford’s biggest projects, won some of the industry’s most prestigious awards, traveled the globe and cemented her reputation as both an industry pioneer and innovator.

Now, following the recent release of her autobiography, What Do You Mean a Black Girl Can’t Design Cars?, King is not only sharing the story of her breakthrough legacy — she’s adding to it.

Having departed Ford in 2008, King says she spends many of her days mentoring young people, particularly girls, hoping to fan their interest in art. She’s also a fixture on the speakers’ circuit, sharing her story and promoting her book. And she’s hoping to one day found a school for young women.

“It would be an academy called She Did It — for girls who dare to dream big,” King explains.

PLAYING IN THE CLAY

King was once such a girl herself. After setting her ambitions on joining her dad at Ford as a car designer, King says, her path was constantly littered with critics and naysayers, minds too small to chart the trails she envisioned herself blazing.

“A lot of times my male teachers would say, ‘What is it that you want to do when you grow up?’” King remembers. “And I would always tell them, ‘I want to be a car designer. I'm going to work for Ford there with my father.’ And a lot of my male teachers would tell me, ‘Oh, no, Emeline. Girls cannot draw cars. You need to take those little hands of yours, and you should be either a librarian, a nurse or a good housewife. But as far as designing cars, girls can't do that.’ Little did they know that my father was exposing me to the world of transportation design.”

In fact, her parents had been exposing her a world of art and design that was much broader, diverse and vibrant than what even many of her teachers had seen. For instance, her father, noted local pastor Rev. Earnest O. King Sr., was deeply rooted in both the local music and art scenes. Rev. King was close friends with famed sculptor and WSU alumnus Oscar Graves and often took Emeline and her siblings to visit Graves’ studio. There, she would experience firsthand the power of the clay as she’d sometimes watch her dad assist Graves with a commissioned sculpture.

“Saturdays would be like a little outing,” King says. “At Mr. Graves’ studio, we got a chance to see a Black sculptor. I was so fascinated with the beautiful sculpture pieces that Mr. Graves and my father would design — and I got a chance to dabble in some of the clay. I just loved playing in that clay.”

SHAPING THE FUTURE

Even as she was shaping the clay, King was herself being molded. The more she dabbled, the more her dreams and determination hardened. By the time she was a student at Detroit Cass Technical High School, King was focused heavily on commercial arts, sculpture and graphic design.

“I would draw people, cars, anything,” King says. “But it wasn’t until I enrolled in Wayne State did I really get training related to transportation design. As I was going to Wayne State, my father had a bunch of his coworkers — and these were Black car designers, Black clay modelers — who mentored me. So I was getting Design 101 there.

“And the unique thing about going to Wayne State, I would take my academics in the daytime and then at night Ford Motor Company had it where some of the transportation designers would come down to the school and offer transportation design classes.”

She also credits WSU with having a huge influence both on her work and on her love for art.

“Wayne State shaped me immensely,” King boasts. “First of all, I liked that it was in the cultural center. You were surrounded by the museums, by the library. And going to Wayne State... I'll never forget. I was infatuated with art history. I just loved art history. And like I said, there was also the advantage of having some of the car designers from Ford Motor Co. come and teach there in the evening. Then, in the morning, I would have my regular sculpture, painting classes, printmaking. Wayne State definitely was a launching pad as far as my career is concerned.”

King says she also was getting life lessons from many of her father’s friends. Graves, for one, urged her to get out of the United States for a bit and spend time abroad.

“When I would go to his studio, he would always tell me, ‘King, you have to go to Europe. You have to be indoctrinated with the European flair,’” she remembers.

But King was laser focused on the goal she’d set at 11 years old. Right after graduation, armed with a portfolio filled with oversized, 30” x 40” car illustrations, King applied for a job at Ford.

“So I had my portfolio,” she says. “Now, the average portfolio is like 18” x 24”. I was drawing big pieces of illustrations, humongous. I did that to get your attention. It was just so impressive seeing these big car drawings on these massive pieces of cardboard. My father was able to get a couple of materials. He would bring it home, and I would use that.

“But when I presented all my car designs,” she says, “they did not believe that those designs came out my head. A lot of the drawings were 10 years ahead. These were the cars that I was designing.”

But even as she awed disbelieving Ford execs with her work, King was unable to land a job right away with the automaker. An economic downturn had slowed hiring at Ford considerably.

Still, King persisted. A meeting with Jack Telnack, Ford Motor Co.’s vice president of global design at the time, had led her to look into the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., a prestigious school that had been attended by many of Ford’s top designers. Her father helped her enroll in what was supposed to be a two- to three-year program. King finished it in 18 months.

And as soon as she did, she left California and was right back at Ford’s front door, still pursuing the job she’d coveted since childhood. Meanwhile, other carmakers had gotten wind of King’s work and were in hot pursuit. Even as she was flying home to Detroit, executives from General Motors and Chrysler were heading to Pasadena to talk to her.

“The school’s director had told me there were a lot of execs coming out there to see my work,” King recalls. “And I told him that I appreciated them coming, but I had promised Mr. Jack Telnack at Ford that I would be interviewed by him. The director told me I was making the biggest mistake. Oh, he was so mad. But I wanted to keep my promise.”

BREAKING THROUGH

Her choice wasn’t a mistake at all. Shortly after her interview with Telnack, King landed the job. She had officially become Ford’s first ever Black female transportation designer.

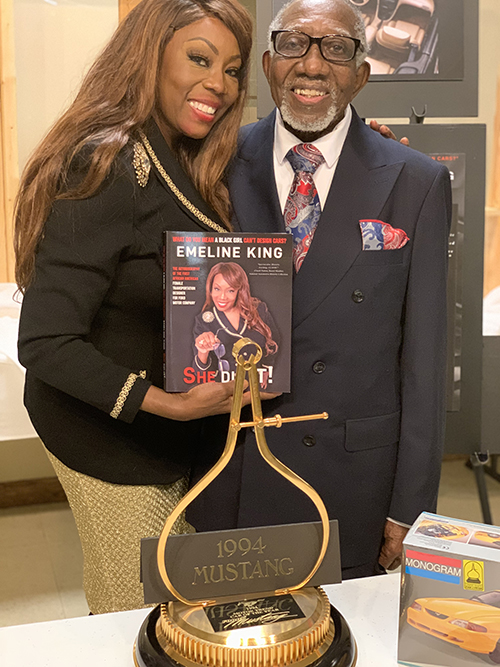

And even as she was making history, she was also getting a chance to meet history. Right after she was hired, King recalls, she wound up meeting a man named McKinley Thompson — who had had the distinction of being the first Black man hired as a transportation designer at Ford. Like King, Thompson had also attended the ArtCenter College of Design.

“I thought that was neat — even though I wasn’t actually aware of it when I met him,” she recalls with a chuckle.

It wouldn’t be too long before King was again breaking new ground at Ford. In December 1984, she was sent to Turin, Italy, for a foreign service assignment. Finally, she would be able to absorb that “European flair” that her mentor Graves had gone on about years ago.

She left Italy an improved designer several months later, hungry to showcase her fast-developing talents. And she got the chance to show what she could do when she was tapped for a role in the design of Ford’s upcoming 1989 Thunderbird, for which she designed the wheels, interior and a portion of the exterior.

Beloved for its aerodynamic body and a wheelbase nine inches longer than its predecessor, the car was a big hit with auto enthusiasts. Ultimately, the 1989 Thunderbird Super Coupe was named Motor Trend Car of the Year, a monumental accolade for the entire design team, but especially for King.

“It was a successful car,” King says. And it helped put the first Black woman to design cars at Ford firmly on the map.

But King, who also did foreign assignments in Germany and England between 1987 and 1990, says she wanted more. She dreamed of one day heading up a project on her own, to manage the development of a vehicle as opposed to simply contributing. Somehow, though, the glass ceiling always kept her bigger dreams out of her reach.

“I always wanted to be a part of management,” she says, “but over the years they kept passing, passing. I thought my credentials could get me into management, and my background, but it didn't. So, I would have a lot of meetings with the execs to find out what is it that I need to do. I was passed over I don't know how many times. I would look at the management and say, ‘It's not diverse. It's not diverse.’ But that went in one ear and out the other.”

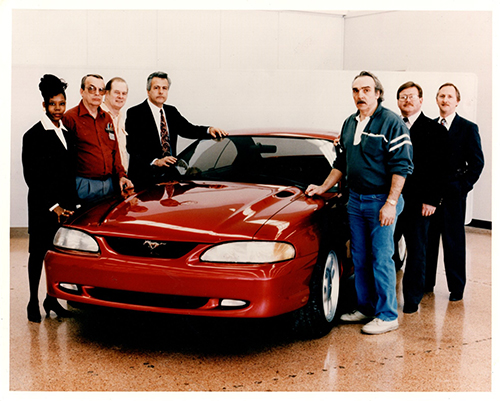

King says a Ford design colleague advised her to get her name tied to a hot project that management would associate with her talent and leadership. But somehow, those opportunities always eluded her — until one day, she found herself working on the vehicle whose iconic, one-word name alone could catapult her into the pantheon of great Ford designers: Mustang.

“We had one staff meeting where we had the designers, supervisors, myself and the engineer (in attendance),” she says. “And my supervisor said, ‘Well, today there's going to be a revision to the '94 Ford Mustang. This is a hot project.’ I had to get on that.”

King says she was added to the team after her supervisors agreed to keep her on from start to finish and to allow her to bring a strong, female perspective to the initiative. So how’d it turn out?

“It was a landslide,” King exclaims. “Every time the word ‘Mustang’ would come up, they related that to Emeline King. I would do a lot of PR work. I mean, a lot of PR work…I was doing interviews. They had me in magazines, on TV shows. And every time they would say ‘Mustang,’ my name would pop up.”

THE NEXT CHAPTER

In the years that followed, King’s success on the Mustang led to work on other major vehicle designs, from the two-seater Thunderbird to the early iterations of the Lincoln Navigator SUV. She earned more praise, more notice, more impact. But somehow, her success never translated into the management role she so deeply desired, says King.

By the early 2000s, King’s circumstances began to change drastically. She was moved out of the design department and into marketing, she says. Not long after that, in 2008, she endured an “involuntary company separation” from Ford, accepting one of the many buyouts the auto manufacturer was offering veteran employees as part of its attempt to trim its workforce and reorganize the company. She admits that she didn’t want to leave but had little choice.

“It felt like the bottom fell out,” King says. “They wanted to downsize. They took me out of the creative part. I didn't mind doing the marketing, but I couldn't do the creative part. And shortly after they moved me out there, it wasn't too much longer when they... when my boss mentioned to me that they're doing the involuntary company separation.”

And with that, the first Black woman to design cars at Ford drove off into history.

Even so, King says she remains appreciative of her two-decades-plus career at Ford and grateful for the opportunities she did receive to showcase her talents. She still shows up for certain events. And she is still friendly with company officials, who she says have been supportive of her post-Ford work and especially her book. In another nod to her impact, King's work also has been featured as part of an exhibit at the Detroit Institute of Arts called “Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950–2020.”

She experienced her share of ups and down along the way, she says, but she loved the ride. And she encourages all the young people she meets not to hesitate to take the wheel of their own lives.

“A lot of times when I go and do a lot of career day speeches at the schools, that I let them know that if I can do it, you can do it,” King says. “The opportunity is there. I found it as a little Black girl from Detroit. I tell them, ‘People or mentors are like bridges. You grab ahold of one of those bridge, be influenced by mentors — or just look at what is it that you want to become — and you don't let anyone tell you what you can't do.”