Those who eat fish two or more times a month from the Detroit River have higher levels of mercury, PCBs and dioxins.

People who eat fish from the Detroit River two or more times per month have higher toxin levels in their blood and urine than national averages, a recent state health department study showed.

Blood and urine samples taken from 273 frequent river anglers had two to three times the average amount of mercury and PCBs, as well as elevated dioxin levels, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

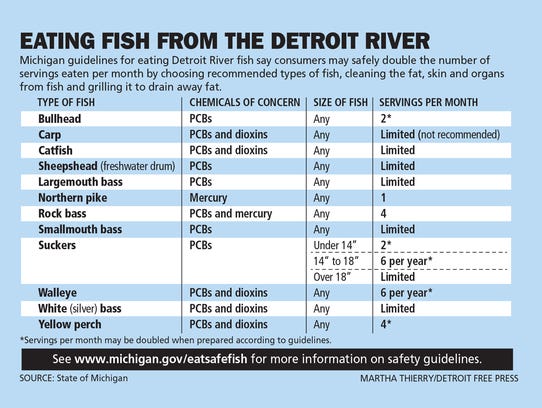

The findings, state health officials say, highlight the importance of following Michigan's Eat Safe Fish guidelines, which list the toxins suspected in different types of fish and how many meals of those fish are safe to eat in a month or year. That may be easier said than done for many metro Detroit families who rely on fish they catch from the river as a food staple.

Detroit resident Ronnie Gotcher, 59, said he has fished the river his entire life and fed himself and his wife and kids from it. As he cast a line for walleye at Riverside Park March 21, he shrugged off the health department's survey results.

Ronnie Gotcher, 59 of Detroit fishes on the Detroit River on Tuesday, March 21, 2017. (Photo: Eric Seals/Detroit Free Press)

"Everything else is the same way — if they did a survey with beef and chicken, you'd find a lot of the same things," he said. "The water, the air we breathe, the ground; they done polluted everything, man. You're not getting out of this. It is what it is, as far as I'm concerned."

The toxins are known to persist in popular fish such as walleye, catfish, bass and northern pike — and they're known to harm human health. Mercury can harm the brain, nervous system and kidneys; PCBs and dioxin are known carcinogens. Fetuses, children, elderly people and those with pre-existing health conditions are the most at risk.

It isn't just a Detroit River issue, said Sue Manente, a health educator with the state health department.

"It’s the same fish, moving up the system," she said. "It doesn’t matter if you’re catching them from Lake Erie, the Detroit River, or moving up to Lake St. Clair."

Similar recommended eating restrictions exist for fish caught throughout Michigan and the Great Lakes. Even fish bought at a restaurant or supermarket — where no mention is typically made of the recommended limited consumption — can expose frequent consumers to potentially harmful chemicals.

Michigan guidelines for eating Detroit River fish say consumers may safely double the number of servings eaten per month by choosing recommended types of fish, cleaning the fat, skin and organs from fish and grilling it to drain away fat. (Photo: Martha Thierry/Detroit Free Press)

The health study was conducted in 2013 and 2014. With assistance from Wayne State University, Detroit River anglers were recruited at fishing spots up and down the river. A similar attempt was made in the Saginaw Bay area, but ultimately proved unsuccessful, Manente said.

Higher levels

A total of 287 adults participated in the Detroit River Urban Fishing Study, Manente said.

The Detroit River anglers tended to follow U.S. Census demographics for the area, said Jennifer Gray, a toxicologist with the state health department: 82% African American; 39% with household income less than $25,000 per year; 18% with less than a high school diploma or GED. Ultimately, 273 people completed the department's questionnaire and provided blood and urine samples, which were evaluated at state health department and federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratories.

John Roseman, 42, of Farmington Hills casts his rod on the bank of the Detroit River at Belle Isle on Tuesday, March 21, 2017. (Photo: Eric Seals/Detroit Free Press)

The results, which were shared with participants, were compared with the CDC's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, or NHANES, a series of health questionnaires and medical examinations given to residents throughout the country, providing a national baseline average — though Manente noted the levels of fish consumption among NHANES participants are unknown.

The Detroit River testing results showed blood mercury and levels of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls, an industrial pollutant) at two to three times greater than the NHANES levels. While exposures to the toxins could come from other sources, river fish are the suspected culprit, because the greater the amount of Detroit River fish a subject ate in a month, the higher their levels of the chemicals. The contamination also came from a type of mercury known as methylmercury, which is the type stored in fish tissues.

"Our study results suggest that this is an exposed population," Manente said. "The total blood mercury and PCB results for the participants suggest exposure to methylmercury and PCBs by eating fish."

Dioxin levels were similar to the national average, but higher in Detroit River fish consumers, the survey showed.

The older the study participant, the higher their toxin levels.

"It could be people had more years exposed to the chemicals, or that people at some point were exposed to the chemicals and it just stuck with them," Gray said.

No so-called action level has been set by federal or state regulators for PCBs and dioxin, above which immediate medical intervention is recommended.

"We know they can harm human health, but the exact amount (that does it) has never been determined by science," Manente said.

But the state health department does have an action level for mercury — 15 micrograms or more per liter of blood — and "a small number" of survey participants exceeded it, she said.

"We sent them letters as soon as we received their mercury results — we didn’t wait until we had all of the results back," Manente said. "And we said, ‘Your mercury levels are pretty high; you should go see your physician.’ There is a medical treatment available."

Detroit resident Jimmie Jackson, 71, participated in the health department's survey. He has fished the Detroit River for about 20 years, and while he's going less frequently now, "the year before that, I was going every day," he said.

Jackson said he ate fish from the river up to twice per month. His test results showed elevated levels of the toxins, "but not to the point where I had to bite my nails and run and see my doctor," he said.

Jackson said he'll look to adjust his habits as a result.

"I'm still going to fish, but I'm going to consume less of the silver bass and go more for yellow perch," a safer fish, he said. "Or, I'm going to try to do more catch-and-release."

Silver bass

To understand the difficulty of translating the alarming survey findings into modifications to people's Detroit River fish consumption, look at the white bass, known locally as silver bass, one of the most popular fish caught on the river. The fish's run up the river from Lake Erie in the spring prompts a major influx of anglers. But the silver bass has a Safe Fish Guideline rating from the state health department of "limited," because of the way it stores PCBs and dioxins in its body.

For the most at-risk populations — children, fetuses, people of reproductive age, and people who already have a serious health condition, such as diabetes or cancer — the limited rating means "we really don't want them eating these fish at all," Manente said.

"And if you don't fall into one of those groups, we say it's OK if you maybe eat them once or twice a year."

But during the height of the silver bass run, Manente said, she had survey participants telling her they ate the fish up to 120 times in a month — "breakfast, lunch and dinner."

"If you know anything about the silver bass run in the Detroit River, you know how many silver bass come out of that river. And how many people have freezers full of silver bass, community fish fries," she said.

Ali Shakoor, a PhD student in Wayne State University's Department of Biological Sciences, interviewed more than 200 Detroit River anglers in 2015 as part of a university program related to the Eat Safe Fish educational efforts on the river.

"There was a large amount of subsistence fishing going on," he said. "Also, there were quite a few individuals who fished a lot and did not consume it; they sold it. There are a lot of people that rely on, specifically, that white bass run to put food on their table. That really subsists their family — not just during that run, but for the entire year."

Because the health effects of the toxins aren't typically immediate — and may never arise — some river anglers don't take them too seriously.

"My grandmother is 92 years old, and she eats fish out of the Detroit River," said Jayson Harris, 46, of Detroit, as he fished on the river March 21.

Harris said he does try to follow the guideline to eat smaller fish rather than the larger, "trophy fish" that often have higher levels of the toxins.

"I'm not going to eat it, and I'm not going to feed it to my family," he said.

But that doesn't mean no one else will.

"Bigger fish, I take a couple of pictures of, sometimes I give it away; sometimes I sell them," Harris said.

Fishing the river from Belle Isle, John Roseman, 43, of Farmington Hills expressed surprise at the survey findings.

John Roseman, 42, of Farmington Hills stares out onto the Detroit River watching his line hoping for a bit on the bank of the Detroit River at Belle Isle on Tuesday, March 21, 2017. (Photo: Eric Seals/Detroit Free Press)

"I had thought things had improved; this kind of suggested to me, perhaps not as much as I'd thought," he said.

Roseman said he tries to follow the state's Safe Fish Guidelines and has avoided eating catfish caught from the river as a result.

Roseman didn't know the popular silver bass he often catches and eats was one of the fish recommended for limited consumption.

"I think it's reasonable to adjust according to that information, I actually do," he said.

No labels

While Eat Safe Fish Guidelines are posted on the state's website and at spots along the Detroit River, one place the recommendations won't be seen is in the supermarket or fish market. Regulations there shift to the Food and Drug Administration, which has no requirements for labeling fish with safety recommendations.

"You can go to any fish market in Eastern Market, there’s a ton of silver bass and catfish that have come from Lake Erie," Shakoor said. "They have ‘limited’ consumption, which is basically no consumption, but yet they are freely being brought into these communities so people can consume them."

The health department also offers a brochure for eating store-purchased fish safely, Manente said.

There's also a lack of uniformity to consumption guidelines throughout the Great Lakes, even though the fish in question are often moving freely throughout them. Guidelines are handled by the state health department in Michigan; by the Department of Natural Resources in Wisconsin, and by the state Environmental Protection Agency in Ohio.

State officials don't want to discourage fishing, including on the Detroit River, Manente said.

"The river is beautiful; we want people to get out there and enjoy it," she said.

The hope is greater awareness of what's safe to eat, and in what quantities.

"If you really love those silver bass, why don’t you give the perch to your kids? Because the kids are going to be at higher risk than older adults," Manente said.

"If they want to eat the fish, they’re going to eat the fish. But at least we’ve given them the information so that they can protect their families."