Black women are nearly three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women, and most of the maternal deaths are preventable. Black mothers are also more likely to experience life-threatening conditions, including preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, blood clots, and preterm birth and low birth weight. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released reports indicating these alarming figures were exacerbated during the pandemic, along with other health disparities.

While this dire reality has become more widely known in recent years – in part because of the high-profile experiences shared by Serena Williams, Allyson Felix, Beyoncé and others – the Black maternal health crisis is nothing new. And it’s especially serious in Detroit, where the maternal death rate is three times the national average and pregnant Black women are 4.5 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women. The current Black maternal mortality rate is 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared to 32.9 deaths per 100,000 as the national average and 26.6 deaths per 100,000 for non-Hispanic white people.

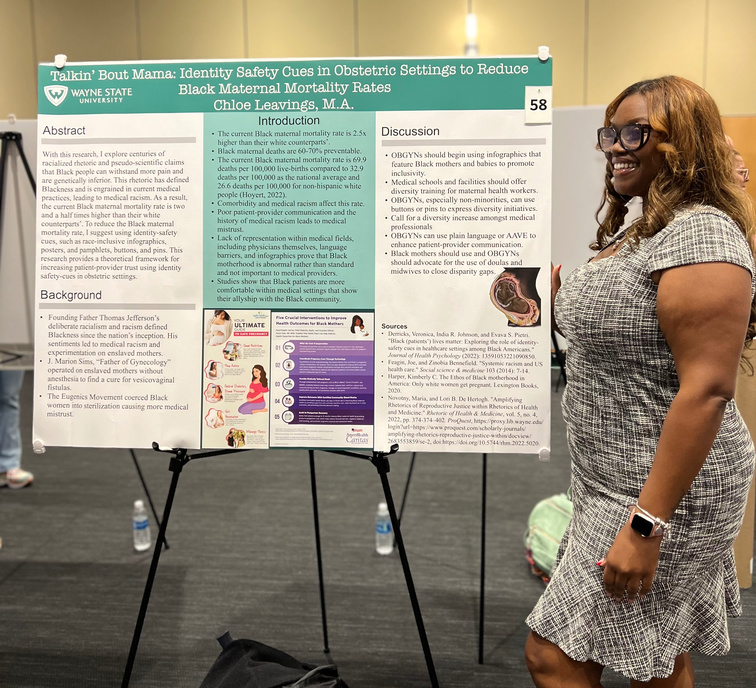

In keeping with Wayne State University’s commitment to community health and addressing health disparities, advocates across campus are working to combat lingering structural and systemic racism in American health care – and the subsequent medical mistrust. Much of that important work is led by health professionals, but Chloe Leavings is looking for solutions beyond the traditional medical perspective.

She wants communication to play a key role in improving the experiences and health of Black moms and their babies. Leavings, who is a Ph.D. student studying rhetoric and composition in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ Department of English, has focused her research on linguistic justice and the rhetoric of health and medicine with her project, “‘Talkin' bout Mama: Identity Safety Cues in Obstetric Settings to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality.”

“I’ve heard the conversation around Black maternal health from a medical perspective – that’s hugely important and it’s absolutely going to save lives,” she said. “But how else do we solve this problem? How do we unlearn decades of medical racism? How do we fill the gaps in health care more broadly – if patients don’t feel comfortable in health care settings and aren’t getting the necessary information in accessible ways, it’s an injustice that can have life-threatening outcomes.”

Leavings’ work, under the guidance of faculty mentor Professor Richard Marback, explores the use of identity safety cues to signal to Black mothers that they’re welcomed and cared for in a health care setting, including:

- The use of diverse, representative infographics

- Physicians openly displaying a commitment to supporting Black mothers, such as wearing a Black Lives Matter button

- Continuous DEI training in clinical settings to help professionals “unlearn” implicit biases and confront systemic racism

- Accessible and open patient-provider communication

- Additional advocacy for Black mothers throughout pregnancy, birth and postpartum by a designated support person like a trained doula

“We need to look at how we communicate with Black moms – what we say to them, about them and – most importantly – how we speak with them and listen to them. We need to build trust,” Leavings said. “Poor communication or lack of communication is at the root of many preventable health issues.”

Leavings plans to build on her theoretical framework from this project in her dissertation, which will look more broadly at the patterns of language used to characterize Black mothers.

A Detroit native who holds two degrees from historically Black universities and a Dean’s Diversity Fellow, Leavings is committed to fighting racial injustices. The work is especially important to Leavings, who accompanied her pregnant mother as a child to the hospital and watched as multiple health care professionals ignored her mother’s own health and pain assessments. While her mother and younger brother were thankfully healthy, the experience still resonates.

“She was having contractions and she had to convince them she was in pain. She needed an IV, and they ignored her when she told them where her best vein was. She told them she had gestational diabetes and they put glucose in the IV. My mom got very sick and had an awful experience,” she said. “It was scary. But it’s even scarier to think about how it could have been worse. It is worse for so many Black moms and it doesn’t have to be.”