Professor, youth activists creating mobile Detroit abolitionist museum exhibit

Inextricably linked to their communities, museums play a unique role in simultaneously preserving the past and holding space for current issues. But what goes in a museum? Who are exhibits designed for? And, perhaps most importantly, who makes those decisions?

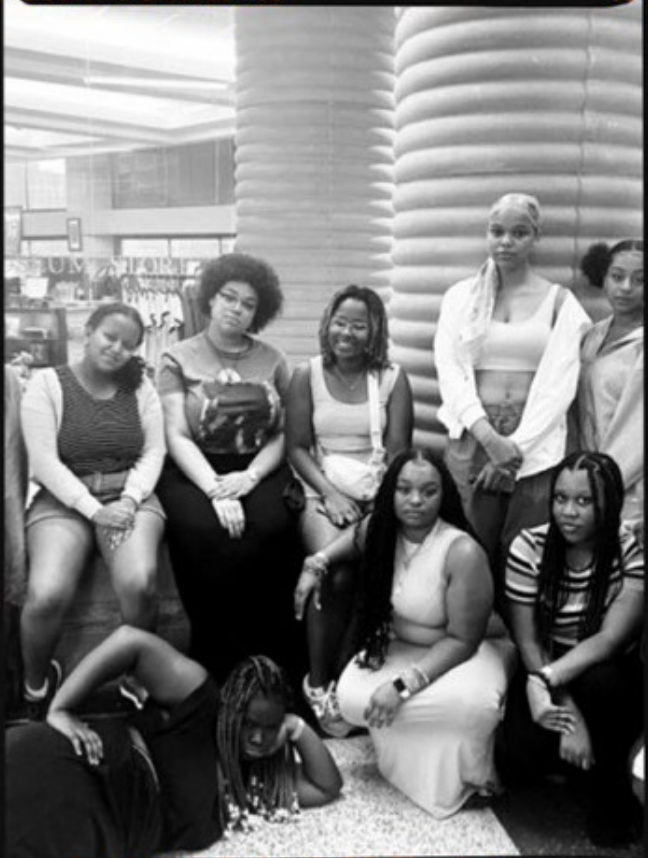

Under the guidance of Aja Reynolds, community activist and assistant professor of urban education and critical race studies in Wayne State University’s College of Education, a cohort of young Black girls spent the summer asking those questions and planning their own pop-up museum exhibition celebrating Detroit’s rich abolitionist legacy. Funded through a grant from Humanities Without Walls and led by community organizations Detroit Heals Detroit and Detroit Area Youth Uniting Michigan (DAYUM), the project empowered Black girls to think critically about museum spaces while researching Detroit history and creating their own telling of it.

The project is one of three funded by the grant, which also supports universities working in partnership with their communities — as “Communiversities” — focused on freedom initiatives. Other projects include the establishment of Freedom School family programs in Chicago and the launch of school curriculums to teach about the prison industrial complex in partnership with individuals released from prison following wrongful convictions in Cincinnati.

“There’s such powerful and amazing freedom work happening in Detroit. It’s beautiful to have these girls at the forefront of telling the bigger narrative around how abolition has been a part of the city’s development and the role it plays in our ongoing progress,” Reynolds said. “Too often, Black girls can be left out of conversations about social progress, even though they’re usually the first to raise their hands and be on the front lines organizing and doing the work.”

Last summer, Reynolds worked with a cohort of 11 girls, ages 14-18, studying abolitionist theory and history and the role of critical archives in movement work. The group visited local museums, including the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History; toured Detroit’s Underground Railroad and was in conversation with a former Detroit Institute of Arts curator. They met with archivists, curators and community leaders to understand how personal experiences are translated into public histories.

“The girls didn’t realize it right away, but the experience was a reflection of a healing moment for all of us. We made space for Black girls, and they were able to be their full selves,” said Reynolds. “In doing so, they realized how often they’re in spaces where that’s not case and started questioning what other spaces they may have been made to feel like they were squeezed into.”

Creating space

“Together, we thought about our experiences in museums: what we loved, what we didn’t love, what things were missing, whose stories were being told, and whether we felt as though we belonged,” Reynolds said. “It was really exciting to come into those spaces with the lens of being excited to see the history but to also question how a museum is structured.”

Reynolds noted that a common theme many of the girls experienced was that of surveillance and being watched in public spaces, which she’s witnessed in real time as well. The project aligns with her research, which focuses on Black girlhood and the creation of freedom spaces through art, activism and healing. Reynolds often encourages critical dialogue about subversive spaces, like museums and schools, in her classroom discussions because so many young people are drawn to them and ready to use their power in creating change.

“There’s this hypervigilance when Black girls enter a space. People don’t seem to expect them to understand and appreciate the significance of those spaces — but they absolutely do,” she said. “We have to advocate for them and teach them to advocate for themselves, especially when they’d go excitedly to see exhibitions centered on the Black experience. It’s a contradiction: Museums want everyone to come see this exhibition that’s supposed to be about them and for them, but the space feels really confined and almost like they’re not supposed to be here.”

To address that disconnect, the group paid special attention to inclusivity, observing everything from the diversity of experiences represented by an exhibition’s artifacts to a space’s structural elements. For example, the group reflected on their experience at the Wright Museum’s And Still We Rise exhibition, which chronicles African American history from the tragedy of the Middle Passage to the heroism of the Civil Rights Movement.

“It’s an emotional experience, but there weren’t any tissues or a designated place to sit as a group and reflect,” Reynolds said. “The girls really took this opportunity to think intentionally about how they can help people feel connected and cared for in our space.”

A compassionate attention to detail and inclusivity is embedded in the group’s plans for an intergenerational mobile exhibition about Detroit’s abolitionist history. The group compiled a zine highlighting their personal reflections and learnings from the summer, ranging from a curated abolitionist playlist to poems, reflections on intersectionality and more. The group recently received additional funding from Humanities Without Walls to continue their project this summer.

While plans for the group’s forthcoming mobile exhibit are underway, the cohort knows for certain one element that must be present: joy.

“It’s inspirational that the girls are so intentional in wanting their exhibit to have joy and hope,” Reynolds said. “They can understand through this experience how people can engage in struggle and still find joy.”