In Detroit, Paradise was lost more than a half-century ago.

A thriving community of Black-owned homes and businesses that had boomed to life in the wake of the nation’s Great Migration of Black Americans from the racist South to the fast-industrializing North, the city’s Paradise Valley neighborhood was swept away in the late 1950s and early ‘60s by a phalanx of bulldozers and construction cranes that razed the area — along with Black Bottom, the major African American residential neighborhood at the time — in the dubious name of “urban renewal.”

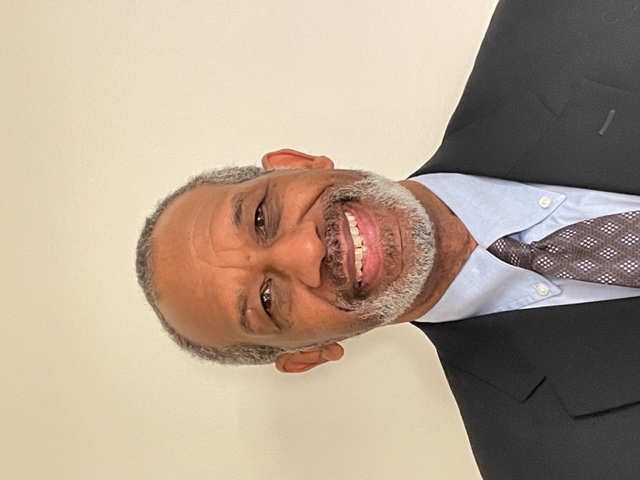

For most of the dwindling numbers of Detroiters who still recall the old neighborhood, Paradise Valley is little more than a fading memory, the stuff of ghost tales about Black-owned hotels, nightclubs and restaurants. But for Louis Jones, Ph.D., archivist at Wayne State University’s Walter P. Reuther Library, Paradise Valley is, in some ways at least, still very much alive.

While the buildings have long since vanished, replaced by the I-375 freeway, Jones and his team have ensured that volumes of information about the community have been preserved in images, official documents and the collected personal papers of those who loved the neighborhood as well as those who had a hand in its destruction.

“We have a couple of collections,” related to the destruction of Paradise Valley, Jones said. “One of them is the Carl Almbland collection. He was working at the City Planning Commission of Detroit, so many of his records in the collection that he donated to us document these efforts to — under the guise of revitalizing the Detroit — force Black people out of their homes and find places elsewhere for them to go.”

Indeed, from the rise and fall of thriving Black communities in Detroit to activist organizations to the freedom struggles and iconic legacies of African American political, social and labor leaders, Wayne State’s archives have for many years been an abundant storehouse for Black historical narratives. As the university prepares once more for its annual celebration of Black History Month, its’ commitment to persevering and promoting Black history is becoming ever more imbued in its institutional fabric. Through the donated archive collections, community service efforts, university classrooms and other initiatives, Wayne State is ensuring that Black history is celebrated, promoted and preserved — not only in February, but year-round.

“WSU students, faculty, staff and alumni promote Black history everyday through volunteer work, courses, events and programs on and off campus,” pointed out Ollie Johnson, Ph.D., the chair of the Department of African American Studies. “The Department of African American Studies, Black Student Union, Black sororities and fraternities, Social Justice Action Committee, Juneteenth Committee, Office of Multicultural Student Engagement, Black Faculty and Staff Association, and many more organizations are putting in work to celebrate Black history and improve the Black community.”

Jones, in explaining his mission as an archivist, noted the timeworn phrase about those who’re ignorant of history being destined to repeat it.

“That’s kind of a trite thing to say, but it’s true at the same time,” Jones said. “Whether it be Black history or any of the other kind of history, you have to have access to records that document periods of history while they were evolving at those very exact periods of history. And there are all kinds of lessons that are learned from reviewing records. I’m often personally inspired by the struggles that I know people went through — Black people in particular — to get to where they got to. And being familiar with those and immersing your soul in those records can be very inspiring for future generations. These records, they tell stories. And we are a repository for those stories.”

Collector's items

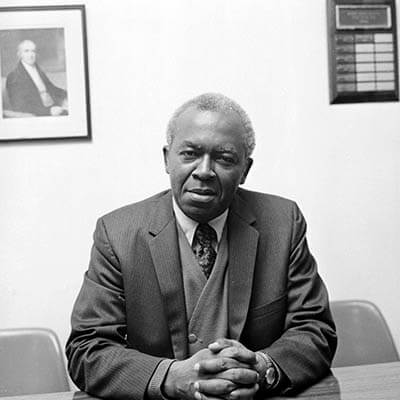

A glance at even a fraction of the WSU archives illustrates the breadth and depth of the many collections that Jones and his team curate. “We’’re the official home for the historical records of the Detroit NAACP papers,” said Jones. “We also have the official repository for the records of New Detroit and Focus Hope. One of the big collections that we have are the papers of Ed Littlejohn, a very prominent law professor who just passed about four or five months ago now. We have the records of Damon Keith, a very famous appeals court judge. We have the records of Ken and Sheila Cockrel. Ken Cockrel

was a very prominent lawyer, very activist radical lawyer, and he defended a lot of people who were charged during STRESS — which stood for Stop The Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets, but was just really an excuse on the behalf of the police department to rough up black folks throughout the city. We have something here called the Detroit Revolutionary Union Movements Collection. And this group was headed up by a guy by the name of General Baker, a very prominent labor activists here in the city, and leader of DRUM, which is the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. This was an effort that took place within the Chrysler plants, the Dodge Chrysler plants, because the Black brokers were always given the hardest jobs, the dirtiest jobs and the most unsafe jobs, and the jobs that paid the least all at the same time, and they’re treated horribly.

“We have records on the ‘urban renewal’ efforts, which were really efforts to remove Black folks from different areas of the city, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley and what have you. Another collection that we have here is the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, which does a lot to document what came after the 1943 race riots here in Detroit. Another of the important collections is that of James and Grace Lee Boggs, very prominent activists and writers here in the city. As a matter of fact, we have a collection already that’s been processed and available for research, but ironically, I’m in the midst actually of collecting more of their records. They have a lot of stuff in what was their home in the east side of the Detroit. So, we have and will be bringing back to the archives probably about 350 boxes of material. And they were not only very prominent activists in Detroit and had their hands in everything related in Detroit, but they had national presence as well.”

Jones, who works closely with the families of many prominent figures to gain access to their works, said that perhaps the largest collection in the archives is the recent raft of documents that once belonged to labor leader Horace Sheffield Jr., grandfather of Detroit City Council President Mary Sheffield. Wayne State acquired the Sheffield collection last year.

Of course, the Reuther’s archives are but one institutional effort to preserve and honor Black history. In 2011, the Wayne State Law School offered a major institutional homage to one of the nation’s most impactful Black jurists when it dedicated and opened the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights. Today, the 10,000-square-foot addition to the Law School building is a hub of education about civil rights law that contains an art installation dedicated to Rosa Parks and is home to assorted programs anchored in the pursuit of racial and social justice, such as the Detroit Equity Action Lab.

““The Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights aspires to be a hub for projects that develop creative methods to further the ongoing pursuit of equal justice under the law,”“ Peter J. Hammer, the director of the Keith Center and the A. Alfred Taubman Endowed Chair at the law school, said not long after the center was dedicated.

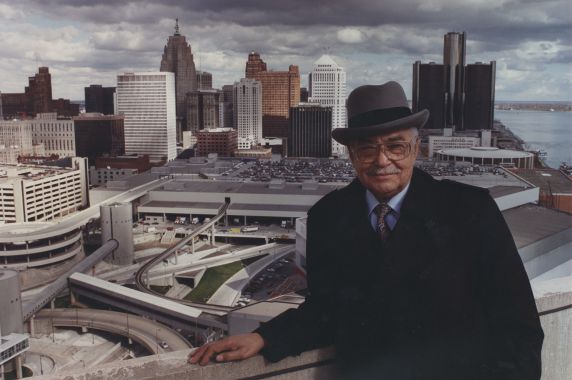

For his part, Hammer has also written extensively about prominent African American historical figures, authoring one biography about Keith in 2013 and a second about George W. Crockett Jr., another powerful African American jurist from Detroit, in 2022. The law school also recently honored another prominent Black legal figure, the recently deceased Edward Littlejohn.

From campus to community

The university’s Black history preservation efforts extend far beyond campus. For instance, several miles west of Detroit, in Inkster, adjunct interdisciplinary professor of anthropology and Near Eastern studies Tareq A. Ramadan, Ph.D., has spent years working alongside community leaders to excavate and rehabilitate the former home of slain civil rights firebrand Malcolm X, who once gave a speech at Wayne State in 1963.

“The home, located at 4336 Williams Street, is the house that Malcolm arrived to in August 1952, and it’s the home where he essentially formally adopts the’ X,’ which was given to him by Elijah Muhammad, the head of the Nation of Islam,” explained Ramadan, who grew up only a few miles from the house. “It’s the house he was in when he begins his foray into the public arena. His brother, Wilfred, lived in the home. He helped facilitate Malcolm’s parole from the Massachusetts Parole Board in ‘52 to bring him to the house. And that really begins one of the most fundamentally important chapters of Malcolm’s life.”

Ramadan said that, even before he got involved with the house, a local community group called Project We Hope, Dream and Believe (PWHDAB) was actively working to save the property, which had fallen into disrepair, from being demolished. Hoping to help somehow, Ramadan, in 2020, called Aaron Sims, the co-founder of the nonprofit that owns the house, and discussed how to secure funds to rehabilitate it. Ramadan joined PWHDAB, then wrote and applied for an African American Civil Rights grant,

which the nonprofit was awarded (through the National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund), in the amount of $380,850, in the summer of 2021, to restore the home to its original condition. Later that year, Ramadan presented the nomination of the home to the State Historic Preservation Office, ultimately landing it on the National Register of Historic Places, making it the first and only of its kind in Inkster.

Since then, the home has undergone a major transformation. “The siding has been changed,” said Ramadan. “The inside has been completely cleaned out and gutted. The roof has been replaced. There’s new wood in the interior. The front facade has been rebuilt out as well, and electricity, gas, a furnace, those things are either concluded or the process of being completed, along with a new driveway, new walkway, new porch, all resized to match the original dimensions of the house.”

In 2022, Ramadan contacted his colleague, historical archaeologist and anthropology department chairperson, Krysta Ryzewski, Ph.D., and founded the Malcolm X Archaeological Project. Ryzewski, who wrote a book on Detroit archaeology, led the excavations and worked with Ramadan to recover artifacts from the site “in an effort to help preserve aspects of the social life of the home”.

Ramadan and Sims, who consulted with Malcolm X’s daughter, Ambassador Attallah Shabazz, on some aspects of the project, said the house will eventually become a museum which will highlight the life of Malcolm and showcase some of Inkster’s African American history. The museum will include some of the items recovered during the excavations, while some artifacts will hopefully become part of a traveling exhibit.

Meanwhile, on the city’s east side, assorted groups of WSU students have spent the last few years working to preserve, at least partially, another local landmark — the sprawling, world-renowned Heidelberg Project,

an eclectic and colorful art installation that, since the 1980s, has earned rave reviews from art lovers in all corners of the globe. In 2023, Wayne State urban planning students began mapping out the future of an iconic piece of local artwork with an eye on preserving its ties to the city’s past.

As a wrap-up to their graduate capstone course, students in the university’s master of urban planning (MUP) program, overseen by the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, delivered a final planning report aimed to help ensure the longevity of the project. In the report, which was presented to Heidelberg staff and community leaders, students offered a host of environmentally friendly recommendations for the art project that would increase foot traffic at Heidelberg, enhance the staff’s resource capacity and enable the redesigned location to support more programming.

Coursework

Similarly, Wayne State offers other courses that allow students detailed, and sometimes uncommon, interactions with African American legacies. David Goldberg, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of African American Studies, has worked in conjunction with the University of Michigan-Detroit and the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights on a “community classroom,” known as Detroiters Speak, that permits students, faculty and the larger public to learn Detroit history directly from those who’ve been involved. His most recent course focused on hip-hop in the city.

Additionally, Goldberg oversees projects in which his student collect the oral histories of Black Detroiters on a range of topics – from neighborhood history and police issues to the 1967 Detroit rebellion and beyond. Goldberg also oversees the Crockett Lumumba Scholars program — a learning community named after the Crockett family of Judge George and Ethylene Crockett and WSU alumnus and late activist attorney Chokwe Lumumba — which seeks to ground participating students in African American Studies and a sense social responsibility.

Further, the professor, who is currently working on a book about radical Detroit labor leader General Baker, contributes to riseupdetroit.org, a Detroit-focused multimedia website that serves as part of the larger Rise Up North Project dedicated to preserving the history of African American fights for equality and empowerment in urban America.

The website lists the Damon J. Keith Center, the Walter P. Reuther Library, and WSU’s School of Library and Information Science as partners in the creation and curation of Detroit-related content.

“We try to put students in a position where they understand and respect the fact Black Detroiters, including their own family members, have made critically important history,” Goldberg said. “Many of the people we learn about have played incredibly important roles in the fight for racial, social and economic justice, be it at an international, national or local level in their families and communities. We are extremely lucky to be located in a mecca for Black history, culture and activism, and we want our students to respect and understand this rich history, while also seeking ways to carry it forward by making their own history.”

Meanwhile, last April, the university announced a three-credit guest lecture series focused on the legacy of former Detroit mayor Coleman A. Young, the first African American to hold the city’s highest office.

The third installment in a series focused on the city’s history, the course introduced students to guests such as former Young administration official Emmet Moten and took a close look at how Young’s early life shaped his views on the city’s development in his administration, including an important examination of Black Bottom, Young’s childhood neighborhood.

Amassing archives

Still, as compelling and thorough as the classes are, researchers and others in search of Black historical narratives — be they political, social or cultural — are invariably drawn to the immense archival work of Louis Jones and his colleagues in the WSU Library System, which maintains Black history collections that date as far back as the 19th century. And while Detroit is, of course, central to many of the library’s archives, the collections cover African American social struggles and cultural contributions from across the nation. Allia McCoy, a social sciences librarian at WSU’s Kresge-Purdy Library, cited vintage papers such as works on San Francisco’s early Black communities from 1870 to 1890 and the Tulsa Race War of 1921. Other papers cover efforts such as the anti-lynching movements in the 1800s and 1900s, and the social migration patterns of Blacks in Boston.

McCoy said that she’s also been focused recently on cultivating a collection of African American food recipes, particularly those gathered by late magazine editor and cookbook author Jonell Nash. Nash, a former editor at Essencemagazine who passed away in 2015, earned fame for creating traditional African American dishes that were both healthy and delicious. She wrote two books, Low-Fat Soul and ‘Essence’ Brings You Great Cooking. Like many of the other archive collections, Nash’s papers and work were donated to the university for preservation.

“It’s all related to African-American culinary arts,” said McCoy. “Some of the books are older, some are related just to soul food or vegan soul food. And I’m just now getting access to this collection. There’s a lot of opportunity to do something with it.”

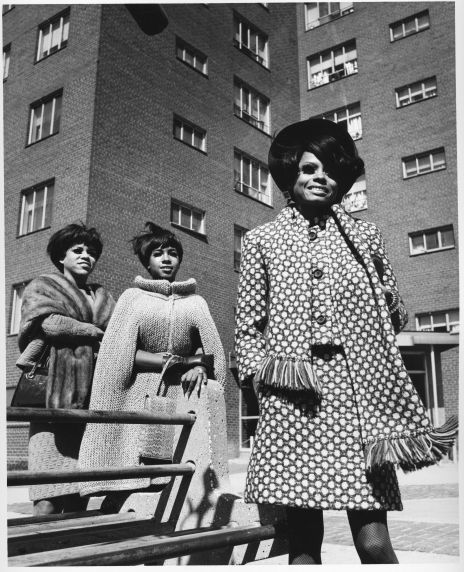

McCoy said she also hopes to expand the cultural collections to include more multimedia entries and to focus on the city’s respected music and dance legacies. She said she hopes to capture figures such as WSU dance professor Karen Prall and local musicians like late rap producer J Dilla. She also hopes to develop a stronger relationship with the record label most closely associated with local music, Motown Records.

“We have a small collection of Motown things, “but it’s modest,” she said. “We should be working with Motown more. We should get whatever archival things they have. Where else, who else, would they work with, if not the school right down the street?”

She admits that her interest in Black musical legacy is as much personal as it is professional. The daughter of jazz pianist Billy McCoy, who passed away last year, Allia McCoy said she hopes to archive many of her father’s personal effects to add to the amplified music collections she envisions. Billy McCoy worked with legendary performers Phyllis Hyman, Pharaoh Sanders, Jean Carn and many others.

“I’d like to do a documentary and get some of this stuff on paper,” she said. “I mean, of course it’s significant to me, but it would be significant to others as well, just because jazz is, unfortunately, not celebrated in our country the way that it should be. Other genres are, but him and his contemporaries are famous in Europe and things like that. I thought about donating stuff to the Detroit Sound Conservancy. We do a lot of work with them. But I’m just more comfortable with the library here because I work here — and because I know they’ll really preserve it.”