Tara Walker admits she was struggling.

It was a late night in 2013, and Walker was frantically poring over textbooks, notes and research papers as she prepared for one of the final legs of her doctoral degree studies: her thesis presentation. With the work piling up, the deadline nearing and the rest of her life responsibilities — a husband, children (one of whom had been newly diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome), her day job — also needing her time, Walker found herself on the phone venting her frustrations with classmate Cynthera McNeill, who, like Walker, was also pursuing her doctorate in nursing practice at Wayne State.

Together with close friend and fellow doctoral candidate Umeika Stephens, Walker and McNeill had, since 2010, slogged through endless semesters of grueling courses and personal challenges that had slowly transformed the women’s three-person study klatch into a relationship that was equal parts professional support network and intimate sisterhood. And, as had always been the case with the three women, when one was in need, one of the others found a way to respond.

So, Walker spilled to McNeill about the difficulties she was facing, about the workload, the time demands and the pressure of finishing the doctoral program on time.

“I was frustrated, tired, pissed off, ready for it to be done,” Walker recalled. “And Cynthera was on the phone like, ‘Well, what do you have to do?' And I was like, ‘She told me to rewrite these last four pages and have it to her office by tomorrow, and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.’ So I'm going on and on and on. She's listening quietly, going, ‘Mm-hmm’ or whatever, and I'm just giving everyone the business. All of a sudden, I was like, ‘Girl, hold on. Someone is at my door!’”

Great, one more distraction, Walker figured as she stalked away from her studies to answer her doorbell. Instead, standing at the door was McNeill, one hand holding her cellphone, the other clutching a bag full of comfort food — Red Vines licorice, nacho chips, pistachio nuts — munchies that the three women had come to refer to during their endless study sessions as their “ride-or-die” snacks.

“She showed up at my doorstep,” Walker remembers. “Never told me she was coming. But she knew I needed her, and she was there. And she stayed on my couch until I finished the last of my pages. She fell asleep a few times, but she kept waking up and was like, ‘Where you at? How is it coming?’ She stayed there. The whole night. She did not have to do that, but she did. Because that’s how it is with us, me, Umeika and Cynthera. That’s what we do for each other.”

As Stephens puts it: “We’ve had all kinds of things happen. But we’re going to be there, without any question. If one of them needs something, I’m dropping what I’m doing. ‘Where you at? Here I come.’ These are my sisters.”

A decade of service

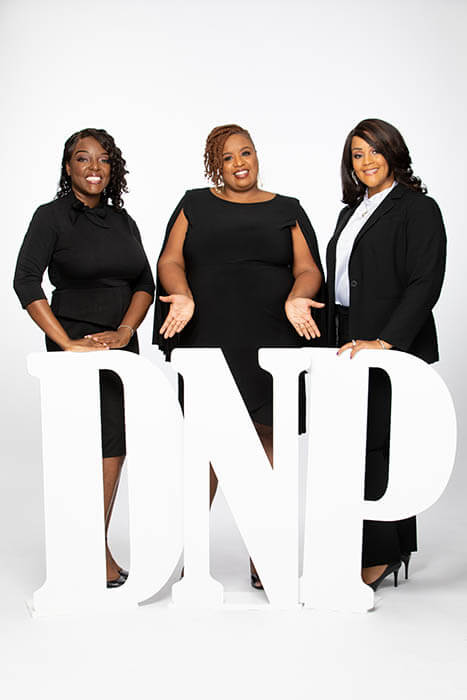

Indeed, for more than a decade, from almost the first week they were enrolled together in the College of Nursing’s doctoral program to today, where all three are decorated professors in the nursing college, Stephens, Walker and McNeill have been nearly inseparable — and unstoppable. The bond that they formed over academics and angst in the early 2010s has become not only a sustaining personal relationship for the three of them — but it’s also the impetus behind a shared vision of community engagement that has seen the three women become driving forces for health education in the city as well as groundbreaking researchers, co-authors, coveted speakers and the cornerstones of a movement to mentor, uplift and empower a whole new generation of African American nurses. Now, as the trio prepares to celebrate the 10thanniversary of their graduation from the College of Nursing’s doctoral program, the women are both looking back on their incredible shared journey and rolling up their sleeves to take on, together, the heavy lifting that remains.

“We’ve been blessed to have had the experiences we’ve had,” says McNeill, the youngest of the three but also the de facto leader of the trio. “It feels good to be able to position ourselves to be a blessing and to work for our community.”

Together, they have created and overseen multiple events and organizations aimed at their dual goals of improving health outcomes in the Black community and increasing the number of Black health professionals in local hospitals and practices. They travel the country together speaking about health issues affecting urban and Black communities. They host health education fairs throughout metro Detroit. And they spend countless hours, both on campus and in the community, sharing advice and inspiration to established as well as aspiring nurses who hope to emulate the trio’s success.

“The Three Amigos is what they call us,” says McNeill. “Everywhere we go, we are well known as this package deal. But it works so well that it's just amazing.”

At this point, the three of them are surprised whenever others are stunned by the strength of their bond. “I'll never forget, we went to this conference in Philly, a Black Ph.D. conference or doctoral conference or something like that, and these women were like, ‘Oh my God, and you guys are friends, and it's organic!’” Walker recalled. “And we were all looking at each other like, What the heck is she talking about? Is there any other way to have a friendship?”

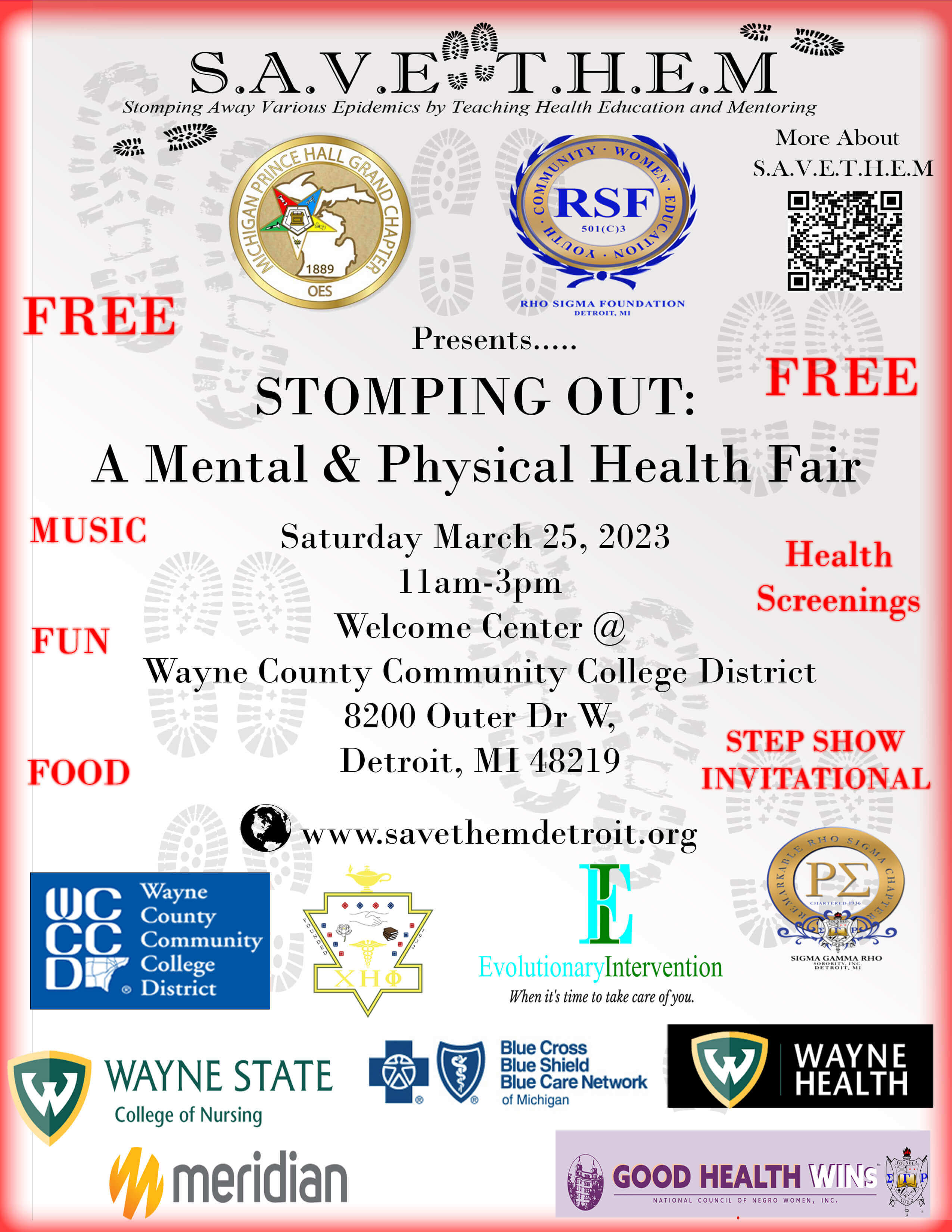

That friendship has led to some Herculean community engagement efforts, including the formation of projects like SAVETHEM, a nonprofit youth education group that sponsors health fairs and other events around the city. There are also initiatives like “No Nurse Left Behind,” a professional mentorship business that McNeill, Stephens and Walker founded and extend to future and current nurses in need of professional advice and direction.

“While we were students, we committed to each other to make sure that we held each other accountable,” said McNeill. “We made sure we were on track to graduate, constantly checking in, making sure we stayed focused and moving through our program. We had an acronym at that time, and we called it ‘NNLB,’ for ‘no nurse left behind.’ We said it jokingly at first, as a way of describing our support for each other. But once we graduated and actually became faculty, we started to hear our students express concerns about feeling as if they didn’t belong or about having psychological barriers that hinder them from progressing in their program. So, we got serious and expanded NNLB.”

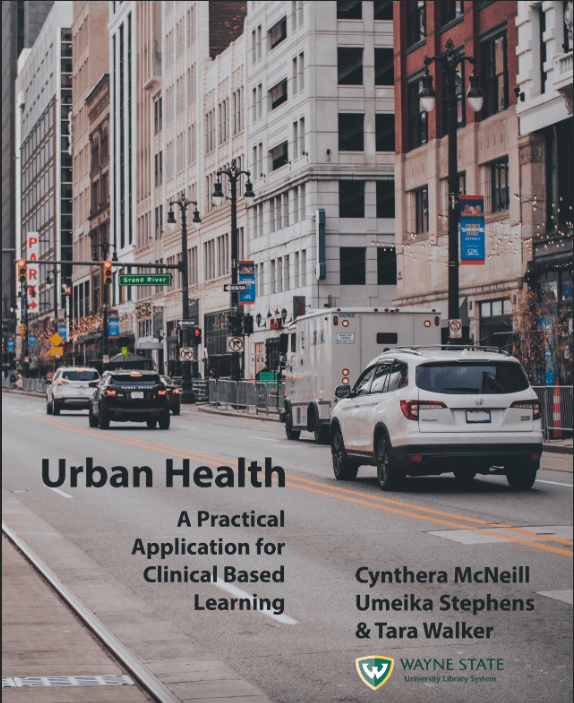

Meanwhile, in 2022, the three of them co-authored Urban Health: A Practical Application for Clinical Based Learning, an increasingly popular online textbook that offers critical and novel insights into the causes and potential solutions for a growing gap in racial health disparities, particularly among urban populations. And, each month, through a program they created called Connecting Our Nurses, the trio gathers students in the College of Nursing for seminars and listening sessions that allow future nurses to air grievances, share their struggles and forge their own support systems. The three also host an annual professional development conference for College of Nursing students. Meanwhile, Walker was recently sworn in as a board member of the Association of Black Nursing Faculty, Inc., and McNeill and Stephens were appointed to the group’s nominating committee. All three have earned significant acclaim across the country, in the community and on campus.

"Drs. Walker, Stephens and McNeill are exceptional educators and practitioners who are well-equipped to lead the conversation on addressing racial health disparities and improving health outcomes in urban population,” Laurie Lauzon Clabo, Ph.D., dean of the College of Nursing, said. “Through their commitment to our students and the individuals and families they serve across our Detroit community each day, they embody the mission and values that guide our college.”

Converging paths

They began as kindred spirits, if strangers, each of them a striver with outsized dreams, each having traveled her own distinct path to the classroom in the Avern H. Cohn Building, where, in 2010, they met as part of their early doctoral studies.

McNeill had grown up in Detroit, a precocious child trying hard to cultivate her academic gifts in a loving but often tumultuous household. She was the middle kid and her parents’ only daughter, born between a set of older brothers and two younger ones. “I’m the girl but they always say I’m the boss.” Unfortunately, she said, chaos at home eventually threatened to derail her promising academic career. So, at 15, while a sophomore at Detroit Renaissance High School, McNeill petitioned for and won the right to become an emancipated minor.

“My situation was, there came a point in my household where the environment was no longer conducive to me being a young person and me learning,” she explained. “There were a lot of distractions. So I made a decision that, in order for me to be successful, I have to get out of this environment. It had nothing to do with whether my family loved me or anything like that. But it was a situation where, with the things that they were dealing with, I could not really focus and concentrate on what I needed to do for my future.”

She found an apartment in Highland Park, worked two jobs after school — careening between an internship as a research assistant at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute and a gig at Kentucky Fried Chicken — and continued to excel in school despite her sparse living conditions.

“I knew I had to work. I knew I had to pay some bills,” said McNeill. “It wasn't lavish. It was a mattress-on-the-floor type of situation. But for me, it was about peace of mind. I had quiet. I had peace of mind. I could think without distraction, and that's what I needed.”

With tremendous support from teachers, family and friends — and despite going to school so exhausted that she sometimes fell asleep in class — McNeill graduated Renaissance with a 3.6 GPA and then enrolled at Michigan State University after earning a full-ride scholarship from the Coleman A. Young Foundation. She graduated MSU, became a certified nurse’s assistant and eventually landed a CNA job at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where she worked with HIV patients.

“That's where I really got introduced to the profession of nursing and to really see what nurses did,” she said. “I really saw how much the nurses really cared about their patients. They were bringing in clothes, bringing in food. What was going on at that time, and even now, was that most people infected with HIV typically have been alienated for whatever reason. Our job was to make them feel safe and accepted. I've seen how the nurses really advocated for their patients and made sure that they had a good-quality experience. That's when I knew I wanted to become a nurse.”

McNeill returned to Michigan intent on re-enrolling at MSU and then going back to Johns Hopkins. “But that wasn't God's plan,” she said. “God's plan had me graduating from nursing school. I applied to Wayne State for the doctorate program, and I got accepted. I've been here ever since.”

Like McNeill, Stephens grew up in Detroit, too, attending “THE Cass Tech High School,” as she still calls it, before graduating with plans to head south to attend either Emory University in Atlanta or Duke University in North Carolina. “That's where I was going,” she said. “But the universe and my parents' checkbooks determined that was not going to happen.” Instead, Stephens said, she wound up at what she called her “fall back school,” the University of Michigan.

She too had initially planned to pursue another medical career, having early dreams of working as a neonatal nurse after watching a special on the profession on an episode of the 20/20 news show when she was younger.

“I didn't see myself as a psych NP then,” said Stephens. “But then we got a chance to work in the NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) as part of a career immersion experience. We had babies die. I'm putting little babies in baby coffins. In my dream, everybody made it. They were coming back when they were 18 and 20 years old, talking about how I was their nurse when they were two pounds. This whole other part, the death, was not where I was at. It wasn't part of my vision. When I graduated, I knew I was going to be a nurse practitioner, but at that point, my interest neonatal nursing was gone."

Meanwhile, her experience at Michigan began rockily as she encountered racism of the worst sort. Said Stephens: “When you grow up in the city, everybody looks like you. Then you leave, and you go to these spaces…. I went to PWIs, primarily white institutions. I had never been in positions where I was judged so immensely based on my skin color or because I lived in Detroit. I went to Cass. Nobody questioned whether I was smart or deserved to be there. Then when I got to college, my freshman year I had crazy experiences. I had been around white people, but I'd never lived around them like this, where it's just me trying to navigate this on my own. They didn't talk to me. I got wrote up (for disciplinary infractions) anytime there was somebody Black near my room, even if they weren't there to see me. It got to the point that I almost got kicked out of the housing system.”

She eventually got her footing and graduated U-M with a bachelor’s in nursing, moving on to earn her master’s degree in nursing from MSU and a post-graduate certificate from Rush University. But Stephens never forgot her early experiences in college, saying that, as hurtful as some of them were, they also helped prepare her both for her career in nursing as well as her future role as a mentor for other nurses also grappling with bias.

“Nursing still lacks a lot of people of color,” she said. “You have to be able to navigate those spaces where people are looking at you based on your skin tone, where there aren’t a huge percentage of Black nurses who are ‘bachelor’s-prepared.’ And to be Black with a doctorate is not something a lot of people see, so you must be confident in those spaces.”

Stephens, who taught at Wayne State several years before entering the doctoral program, said she initially decided to start teaching after having had distasteful experiences with professors who treated students so poorly that they often felt “hazed.” “That’s where my desire to teach actually came from,” she said. “I feel like, as an educator, you should not be making people's experience worse. You shouldn't be coming here feeling like you're the gatekeeper for all nursing and that you're going to make sure we're tough enough to make it. That's not what we do.”

She said she was excited to teach at WSU, both before earning her DNP and after.

“Wayne State has been such a part of my life in terms of coming to programs and things like that in high school,” said Stephens, who is program director of the university’s nursing psychology program. “If you go to high school in Detroit, Wayne State is just a part of your whole experience, especially if you go to a college prep school. You're going to be in some science program some weekend. I was in music, so we were in some weekend music program. We were always on campus. I really have a thing too about urban health and about being able to help people in the city where I've lived my whole life. I mean, if you’re at Wayne State, that's just what you're going to do.”

Tara Walker was reared in nearby Romulus, where she too endured an uphill climb into the rarefied ranks of higher education. Her mother struggled with mental illness, forcing her dad to raise her largely by himself. “And this was back in the 1980s when there wasn't all this talk about being a ‘girl dad.’ He was a Black man working at the plant and his daughter needed him, and he rose to the call, God rest his soul. Because of childhood trauma I endured with my mother, society would say I'm supposed to drop out of high school or become a teen mom based on statistics. I made a promise to myself that I would not be a statistic and that I’d defy all the stereotypes. And that's why I work as hard as I do. And when I share that story, I'm like, ‘You can't change your past or what happened, but you can change how you move forward in it.’”

After graduating Romulus High with honors, Walker went on to study at Howard University, then transferred to the University of Rochester, where she earned her bachelor’s in nursing. After returning to Michigan, she rose through the ranks of nursing management, but, she said, was told by a superior that she had to obtain a master’s degree because “the rules are not the same for Blacks in nursing.” So she went on to get her master’s degree from the University of Phoenix in Southfield. She also remarried and had a third child with her new husband. A few years later, she decided to pursue her doctorate.

“I knew ultimately I wanted to be a nurse practitioner — that's why it was also important for me to go to a reputable university,” said Walker. “And Wayne State met that match. I knew that if people saw Wayne State on my resume, they knew they were getting top quality. When it comes to healthcare, and I’m not saying other schools aren’t good, but Wayne State is near and dear to my heart.”

Walker said her second husband, Donald, was far more supportive of her pursuit of her advanced degree and now is himself earning his doctorate from Wayne State.

“Going back to school was a heavy burden on Donald and our young family,” she recalled. “We had to have that courageous conversation where I explained to him that this degree will require me to be out of the house a lot to study because people would be depending on me, that I’d be the person nurses were calling if a patient started having real trouble. Once it was explained, he was like, ‘You know what? Then do what you got to do. All I ask is that you bring home A’s.’ For three years, my kids lived on baked chicken and green beans on Monday, baked chicken and broccoli on Tuesday. Wednesday, it was baked beans and broccoli with the leftover chicken. Thursday was whatever. And then Friday was Little Caesars. When I graduated, my family was like, ‘I don't want to see baked chicken no more!’”

Together from the start

Of course, for Walker, Stephens and McNeill, their struggle during those three years went well beyond the dinner menu. The coursework was grueling. The professors harbored high expectations. And the toll on their personal lives remained heavy. But their efforts were made even more satisfying not just because of the degrees they earned, but because of the fast friendship they formed not long after their paths converged in class.

“I remember when we had our first class together, a nursing theory class,” Stephens recalled. “In the class, me and Tara sat in the back. I'm a back sitter. I am never going to be in the front row of any class. That's just not me. Dr. McNeill was there in the front. But you know how you know that you have a kindred spirit, just in the way somebody answers a question? I remember being in the class, just the way Dr. McNeill would answer questions, I knew. We ended up working on a project together that next semester. Having been through school, I knew that to be successful, you've got to figure out who your people are. You've got to come in and figure out who is going to be on your team. I was sitting by Dr. Walker, who is the friendliest person. The next semester, we all ended up talking about a paper or something like that. At that point, everybody's just together in every kind of class. Then it was ‘Oh, you want to go to lunch? Let's talk about this paper.’ It became magnetic.”

All three agree that their friendship was critical to their success during their DNP studies. “In hindsight, I don't think that I could have done it without them,” McNeill said. “We didn't know each other prior to applying to this program. When you look at us individually, we have a different background story and a whole different profile. But our genuine passions and commitments are the same. And we connected, I think, after our first semester. So the program started the fall of 2010. Being a doctoral student and really getting into these courses, you just feel maybe some imposter syndrome. You just kind of feel like, ‘What am I doing? How did I get here?’ It seems like it's a very different culture change when you start to look at being a doctorally prepared person and having a terminal degree in your profession. That can just put you in a mindset of, ‘Okay, am I really prepared for this?’ But again, we were doing the classwork as we had to. That second semester we started working on projects together. We started to have more classes together. And then we just started to talk and connect. Initially, we really were about, ‘Let's all motivate and empower each other.’ So it was just more than the three of us initially, just in terms of students that, ‘Look, let's just share knowledge. Let's study together. Let's make sure that we have a support system because this doctoral program is no joke. And we don't want to lose anybody so let's just stay connected.’ We started with more of a broad type of reaching out to everyone that was even interested in trying to be a part of a support system. And then as time went on, the three of us just became true and organic in our connection. We are totally different, but we just meshed so well. We all have different specialties. And that was another thing that could have separated us, but that just brought us together.”

Indeed, Stephens, McNeill and Walker have forged a collaborative style that tied together their three major areas of expertise — McNeill is an adult-gerontology primary care nurse practitioner, Stephens a psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioner who focuses on holistic, patient-centered mental health care, and Walker an acute care nurse practitioner who specializes in internal medicine — and their distinct, engaging personalities. As professional colleagues and friends, each seems to embrace roles that seem both natural to their character and complementary to their collaborative work.

McNeill, for instance, is regarded as the visionary of the group, the one who can be counted on to generate many of the ideas around which their joint work revolves, the group’s biggest source of inspiration and encouragement. For instance, she was the spark behind one of the trio’s biggest recent successes, their jointly written textbook Urban Health, whose digital version has been downloaded across the country. She assembled the bulk of the book’s outline.

“As we constantly say, Dr. Walker and I will blame Dr. McNeill for most things that she gets us into,” cracked Stephens.

Stephens, meanwhile, when it comes to programs such as the S.A.V.E.T.H.E.M. adolescent health fairs, is the hands-on builder of the team, the one who smooths out logistics. She often oversees the group’s scheduling and appearances and brings practicality and determination that help breathe life into McNeill’s brainstorms. “She's the person who says, ‘Okay, the vision is already done,’ and then she makes it work in real time,” McNeill explained. “Whatever it is, if it's speaking at national conferences or if it's a speaking engagement, whatever it is, by the time I get to the real part, I'm burnt out. I'm burnt out with all my theorizing and my thoughts. So Dr. Stephens jumps in with the hands-on, ‘Okay, this is logistics. This is how it's going to go.’ She's there for that. She has a great skillset set for jumping into action and making the pieces move to facilitate whatever you're trying to do.”

Finally, the kind-natured Walker serves as something of a diplomat within the group, the one who knows how to recruit volunteers and supporters to the trio’s assorted causes, the one who upset students often turn to for nurturing, encouragement and a shoulder to sob on. “Because of her charismatic and caring personality, Dr. Walker is able to impactfully engage the public, aligning resources, securing speakers for conferences, networking, engaging students and colleagues to participate, etc.,” explained McNeill. As a result, Walker leads the No Nurse Left Behind and Connecting our Nurses conferences and workshops. She also has a knack for mentorship and event planning. One of Dr. Walker’s strongest traits, McNeill and Stephens said, is her ability to “cross-pollinate,” to bring people together in such a way that their knowledge and skills influence each other’s.

“We have a nickname for Dr. Walker — DNP Dial-A-Friend,” joked Stephens, referring to the Who Wants to Be A Millionaire? game show tactic in which contestants phone friends for help. “She’s probably the friendliest person I know. If she’s near you, she’s going to talk to you. She’s going to ask, ‘Hey, how’re you doing?’ That’s just who she is.”

Added McNeill: “Dr. Walker is going to always try to work with you and help you with what you need. She is the person that's going to engage you on an individual level. When it comes to finding the vendors or getting sponsors or even getting the students to attend events, she’s the person for that. And you can tell that she's genuine. We all are genuine, but I'm a little rough around the edges. She's more of the softer side of Sears.”

Undeniable impact

Together and individually, the three have made an undeniable impact on the community they serve and call home. They’ve heightened community awareness around health disparities and helped bring a homespun common sense to health education among communities too often burdened by poor dietary choices, environmental injustices and not nearly enough access to quality medical care.

In their personal lives, the women are just as vested in the community, both in Detroit and the surrounding area. McNeill and Walker serve as members of the high-powered Sigma Gamma Rho and Delta Sigma Theta sororities, respectively. All three belong to the nursing sorority Chi Eta Phi. Meanwhile, Walker also does extensive work to educate women about maternal health risks and teaches organizations to advocate for ending Black maternal health disparities. McNeill invests in real estate throughout the city and lectures to assorted groups about health issues. Stephens serves at a small mental health practice aimed at providing quality therapy to African Americans.

And of course, they are devoted to raising up the next generation of nurses. “I think the first thing we agreed on jointly is mentorship,” McNeill explains. “We wanted to let our students know that we understand it’s not easy. We wanted to be transparent. We had barriers when we were in school, too, but we got through them — and they can, too.”

This story also appears in the latest issue of Warriors magazine.