According to the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 70% of adults in the U.S. — 222.4 million people — have experienced some type of traumatic event[1] in their lifetime. Per the National Institute for Children’s Health Equity, 34.8 million children — nearly half of all American children — are exposed to traumatic experiences. Aspiring behavioral neuroscientist Samantha Ely is studying how those traumas impact youth, specifically how childhood trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress affect attention-related neurobehavioral responses in children.

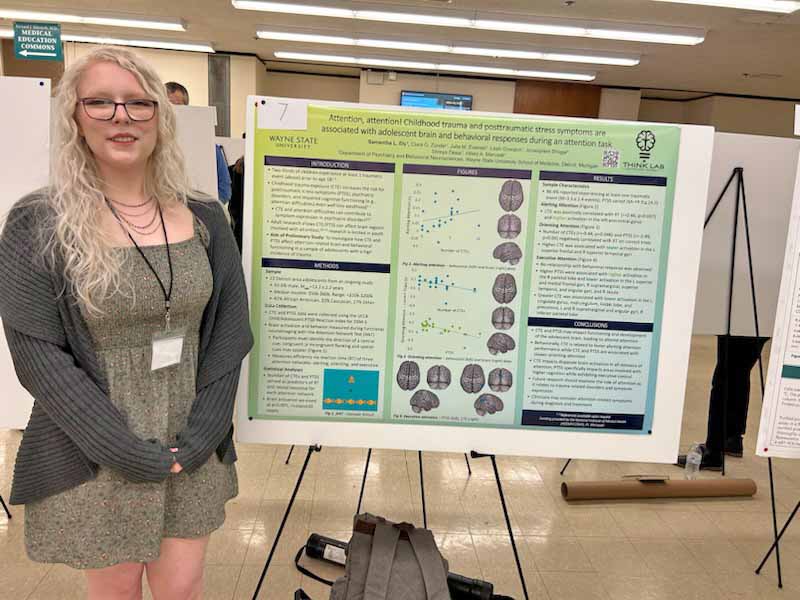

As part of Wayne State University’s annual Graduate Research Symposium, Ely, a first-year Ph.D. student in the School of Medicine’s Translational Neuroscience Program, studied 22 Detroit-area adolescents to determine if there’s a relationship between childhood trauma and impaired cognitive functioning related to attention.

“There’s emerging research in adults to show that exposure to traumatic events in childhood leads to altered functioning in attention-related brain areas that can lead to deficits, but not much is known about how these processes are affected in youth” said Ely during her research presentation.

In an ongoing study, participants were asked about their experiences with potentially traumatic events as well as subsequent post-traumatic stress symptoms. Researchers also measured their attention-related brain and behavioral functioning in response to an attention task, measuring three different modes of attention — alerting attention, orienting attention and executive attention. The findings?[2] Childhood trauma exposure as well as post-traumatic stress symptoms impacted all three attentional domains in different ways.

“The mere exposure to traumatic events in childhood may impact the developing brain, leading to altered attention,” said Ely. “Future research may want to consider the role of attention as it plays in symptom expression and treatment response in trauma-related disorders. In addition, clinicians may want to consider attention-related symptoms while diagnosing and treating such disorders.”

Why this study?

For Ely, who has various interests, the motivation for this particular study came from her curiosity surrounding the vision system. “There’s very preliminary research to show there are disturbances in the vision system once someone is exposed to trauma,” she said. “When digging into the literature, there seems to be more of this spatial attention component that may more so be directly related to trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms.” After even more reading, Ely found there was this huge gap in the literature that looked at how attention is impacted by trauma exposure, especially in kids. “I felt like this gap needed to be addressed,” she added.

Awareness is a large part of Ely’s motivation as well. “There’s a lot of global research to show that many, many people, including children, are exposed to trauma. The number is huge. And I want to know how that experience impacts adulthood,” Ely said. “If we had more of an understanding about what’s going on, we’d be more empathetic about people having mental health issues; it’s not something to be ashamed of.”

Especially for kids, Ely feels it’s of paramount importance to not only do the research but to talk about it. “It’s important to have these kinds of conversations surrounding these experiences that children go through, to shine a light on the fact that these issues are real and something needs to be done about them.”

Why behavioral neuroscience? Why Wayne State?

Though she has a bachelor’s degree in psychology (from Albion College), Ely has always had a passion for neuroscience. “I made all my psychology projects neuroscience-focused. It’s always been integral to me,” she said. With a research-coordinator background (at Michigan State University), she discovered the need for more child-focused research, specifically on how certain events and experiences impact children psychologically and neurologically.

She found that the questions she constantly asked herself — what’s happening in the brains of people who are performing certain actions? What happened in their lives and how does that change the wiring in their brains? — continued to point her in the direction of neuroscience, especially as the field combines a lot of different perspectives from other fields like psychology, chemistry, biology and even philosophy.

When it came to expanding her knowledge and really honing in on her various curiosities related to neuroscience, Ely was drawn to Wayne State’s Translational Neuroscience Program. “The program offers the most well-rounded training I could get, especially because my interests are so variable.” Ely boasted. “I’m definitely very happy with my decision.”

She thrives off that human connection but also loves to work in research. She currently works at the Wayne State Think Lab, led by Hilary Marusak, assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences at Wayne State’s School of Medicine. Ely said she not only loves all the research that takes place in the lab but how Marusak lets her explore her own interests. “She’s been the stand-out piece of my time here so far. She’s a great mentor who has the perfect balance of letting you be independent while also offering guidance and helping her students stay on track and try new things.”

From research, publication and connection opportunities to the freedom to entertain her curiosities, Ely has quickly enjoyed the “very pleasant surprise” of all that Wayne State has to offer. And already, in only one year’s time, it’s clear that Ely’s passion, brilliance and marvels will continue to make a lasting impact, not just at Wayne State and in behavioral neuroscience but in the mental health field and beyond.

[1] Traumatic events can include experiences or exposure to domestic violence, community violence, school violence, sexual abuse or physical assault. For the purposes of the study discussed in this article, the researchers used the UCLA PTSD Reactivity Index to assess for these types of traumas and others such as psychological abuse and neglect.

[2] Adolescents with a greater number of traumatic events had faster alerting attention and higher activation in motor control areas of the brain. Conversely, those with a greater number of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress symptoms also had slower orienting attention, and the number of traumatic events specifically was related to lower activation in brain areas involved in visuospatial attention. Regarding executive attention, the number of traumatic events and posttraumatic symptoms were both generally associated with lower activation in areas involved in higher cognition and processing."

By Katheryn Kutil