After spending nearly 28 years behind bars, 45-year-old Wayne State University freshman Dale Byrd never imagined that he’d have to endure conditions as challenging as the ordeals he experienced while locked up.

But then, in September 2022, Byrd was released.

“When I first came home, I had nothing,” Byrd said, staring somberly into a laptop camera during a recent Zoom chat. “I had to start off in a shelter on Woodward. I had nothing but some books I came home from prison with and the prison clothes they released me with. That was it.

“My family was dismantled when I went to prison almost 30 years ago,” he continued. “I’d lost pretty much everybody that really had a connection and true love for Dale. Initially, I had started developing thoughts in my mind, sitting in that room, that it might be easier in prison.”

But even with so much of his family gone, Byrd nonetheless had walked out of prison and into a support program that has refused to let him fail. For all his troubles post-release, Byrd had been admitted into WSU’s cutting-edge Educational Transition Coordination (ETC) Program, which helps formerly incarcerated people enroll in colleges statewide, and there was simply no way that leadership intended to let him down.

Serving the "justice-impacted"

Designed specifically to meet the needs of recently released inmates, those whom Director Toycia Collins and Coordinator Terrell Topps call “the justice-impacted,” the ETC program has become both a crucible of second chances as well as a conduit for social justice that supporters hope will help undo decades of criminal justice policy by forging something of a “prison-to-school” pipeline.

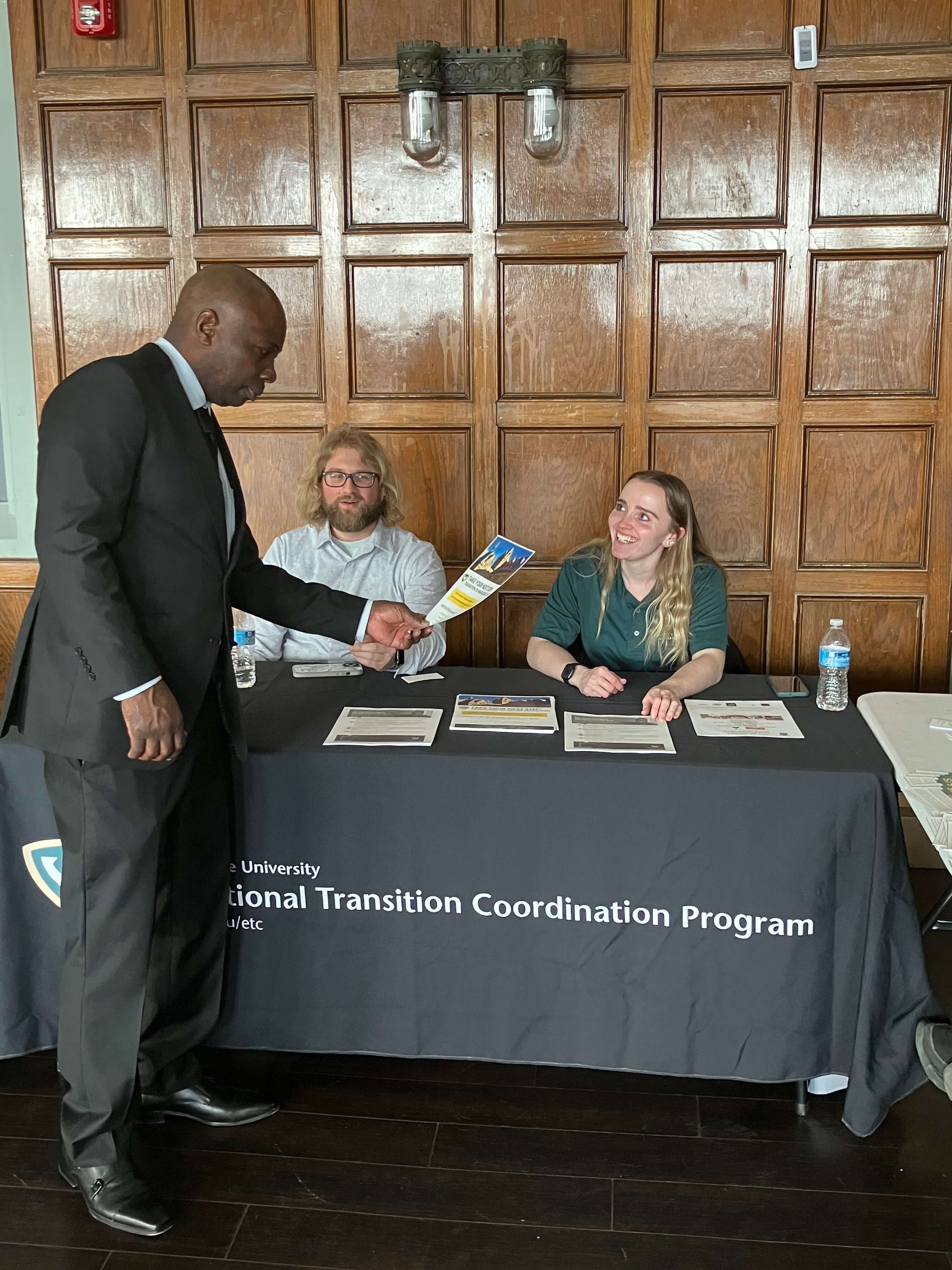

Created in 2021 through a two-year, $200,000 grant from the Michigan Justice Fund and overseen by the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the School of Social Work, the re-entry program has reached out to hundreds of men and women nearing release from statewide correctional facilities to offer assistance in enrolling in postsecondary institutions ranging from trade schools to small colleges to major universities like Wayne State.

Collins said that the program currently hosts 11 students who have been accepted to one institution of higher learning or another, with seven accepted to Wayne State University. And while she’d love to see more become Warriors, Collins explained that the program focuses on a larger objective.

“The hope of the project is to steer these men and women to wherever fits their needs best,” Collins said. “We do understand that sometimes when people come home, depending on when they come home, it may make sense [to enroll at WSU]; for example, we’ve had guys who started collegiate programming while they were inside, but they didn’t finish. We also have to think about the financial portion of things. For some of them, it is not feasible to come to Wayne State, so we are just willing to direct them to wherever fits them best.”

Collins said that, upon release, participants are quickly whisked to a campus to get an early taste of college life.

“We take them to campus just for them to see the dream,” Collins said. “Because oftentimes when you talk to them [while locked up], even though they are from very close to, say, the Wayne State campus, they’ve never been: They’ve never walked the hallways, the walkway — they’ve never done it. So one of the first things we do is take them there just for them to be able to see what’s possible, what the college campus has, where they’re going to be.”

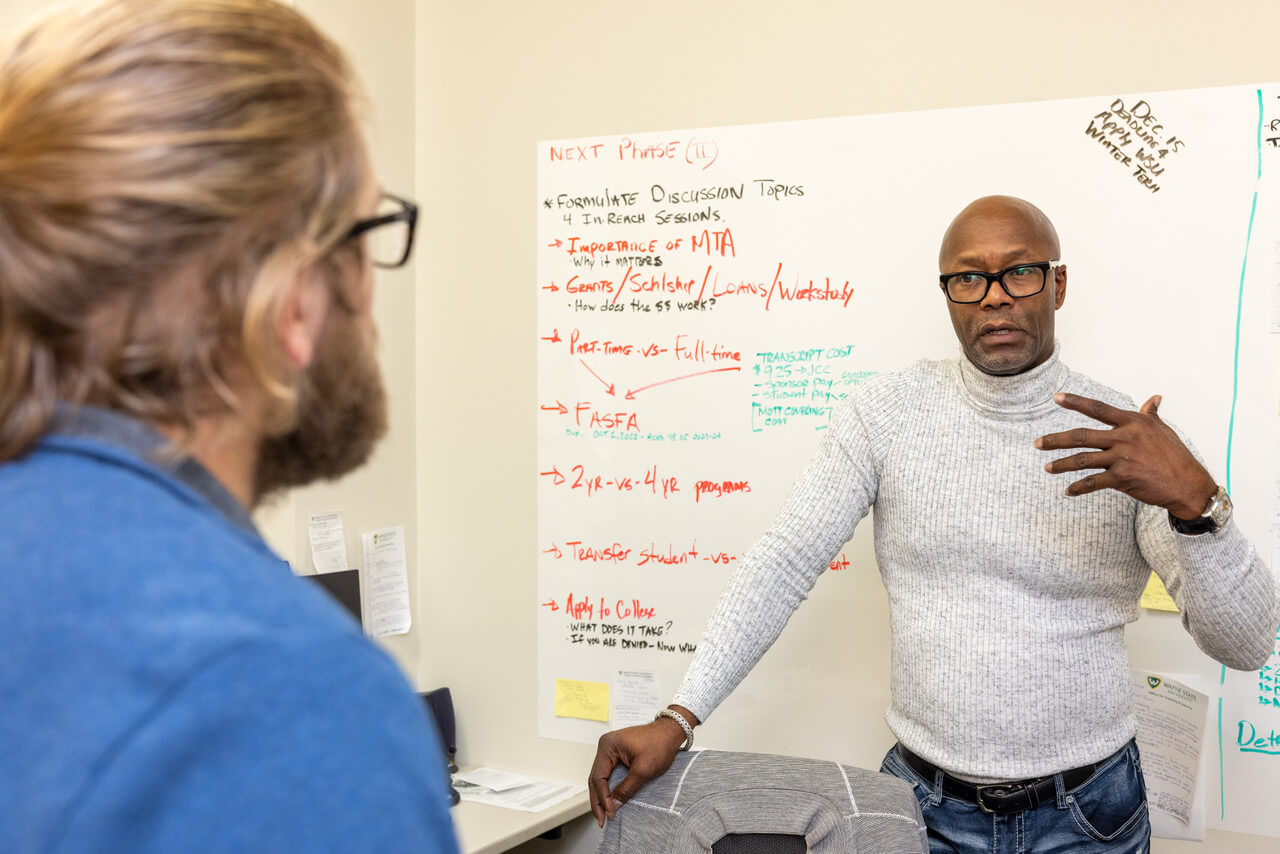

Even before the participants are released, though, ETC staffers — along with Topps and Collins, two "student navigators" and a research assistant also work for the program — visit them in correctional facilities around Michigan to provide hands-on assistance in tackling issues that may be awaiting on the outside. Topps, who visits multiple facilities weekly, noted that he has had to help his charges grapple with everything from shelter and unemployment assistance to financial aid applications and class schedules.

“We reach out to them within 18 months prior to getting out,” said Topps, a WSU alumnus who himself served more than 15 years in prison before earning two degrees, opening a counseling business and taking his position within the ETC program. “The closer they are, the more focused we become with them. In a nutshell, we take their hand and navigate their transition period.

“I [recently] had a meeting with a potential client,” Topps continued. “We were talking to him about what a FAFSA is, what financial aid and financial literacy look like, what transfer paperwork needs to be turned over. We navigate all of those education to-dos in addition to helping navigate these men into community resources that they need.”

Establishing bonds beyond the bars

Byrd, who’d earned three associate degrees prior to his release, said that he was still incarcerated at Cotton Correctional Facility when he first heard Topps talk about the ETC program.

“He did a presentation about what Wayne State is trying to do through the educational transition team, so I spoke up said that I wanted to be part of that,” Byrd recalled. “I wanted to attend Wayne State. I told them I wanted to go to law school there, so we connected and established a bond.”

Topps and Collins helped Byrd fill out his paperwork and get enrolled in WSU — but the ETC staff was also honest with him about his career aspirations. Byrd, who was imprisoned as a young man on several serious felony charges, said staffers reminded him that some professions require licensure and certifications and, thus, participants should be prudent in selecting college programs and career choices.

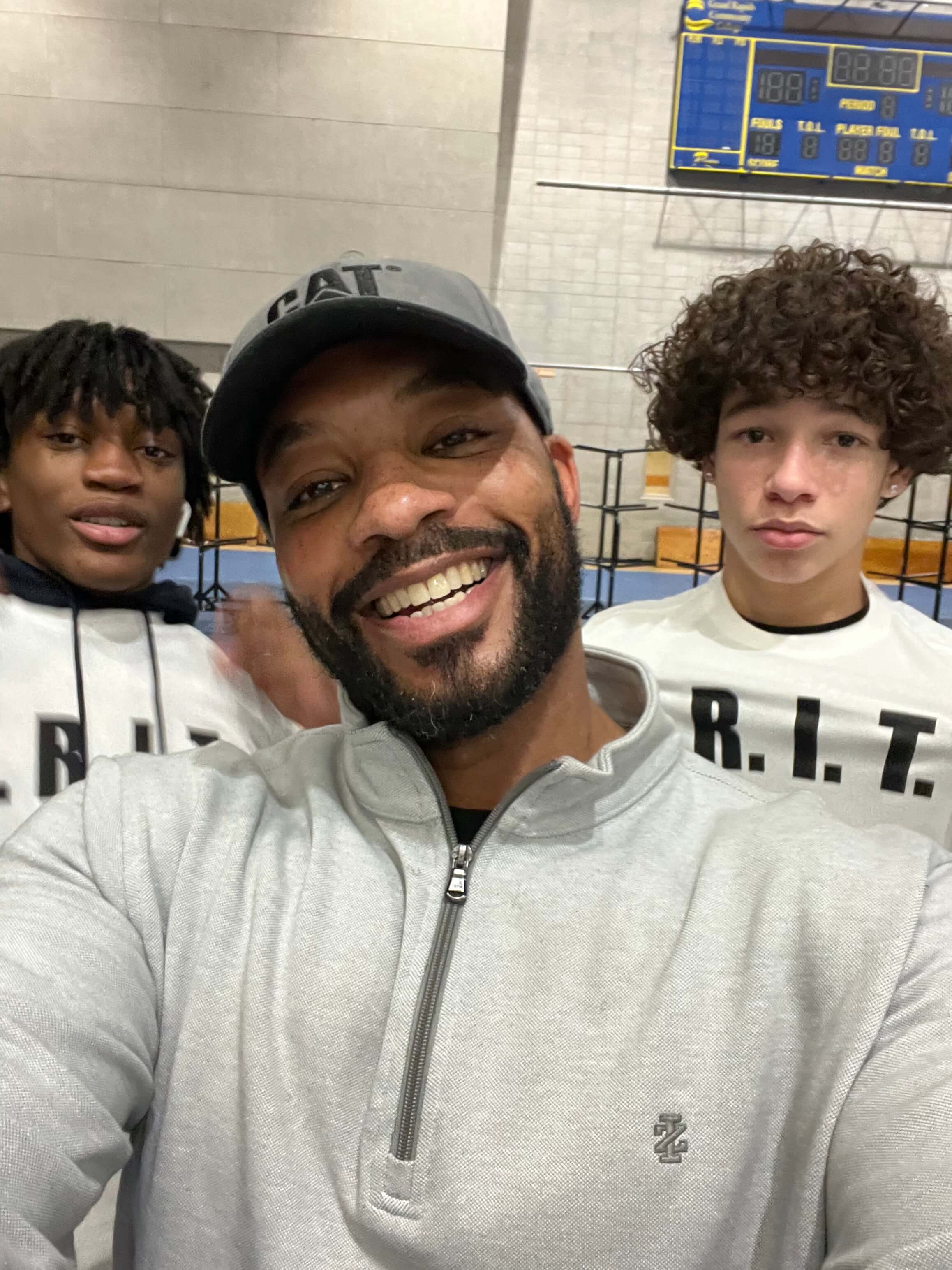

Byrd decided to pursue a criminal justice degree and said he’s discussed a range of other career options with his advisors. He now sees a future in which he works closely with troubled and disadvantaged youth.

“My passion to help my environment comes from the struggles that I had,” said Byrd, who had been in and out of correctional facilities even as a youth. “My passion to want to help young people comes from the fact that I saw boatloads of us go straight through the juvenile system and right into prison. I met so many people in prison that I knew from the juvenile system that it would blow your mind: It’s like a big pipeline, and I didn’t want to carry that on with my life. I want to write a new narrative.”

Byrd observed that his personal situation also has improved mightily. In addition to enrolling at WSU, he rekindled a relationship with an old flame and eventually moved in with her. He tackles odd jobs while he looks for steady work, and he remains in close contact with the ETC team. He said he’s still learning to get acclimated to the digital age — using certain computer programs has presented a particular challenge — but remains determined to earn his degree.

“If it’s new you, you are done with the old,” he said. “You’ve got to push yourself. You have to push yourself past the point of feeling vulnerable and say, ‘This is what I want to do with my life. I want something better.’”

A solid foundation

Even for participants whose home lives haven’t been in tumult, the program has still been a stabilizing force.

For instance, Grand Rapids native Jonathan Roden said that, although he was able to come home to a functional and supportive family after serving a 23-year sentence for several armed robberies on the west side of the state, the ETC program helped him carve out a real path to becoming a Warrior.

“What this program showed me was that there were people who were willing to step out there and not just welcome you back into society, but usher you back into society,” said Roden, who also got a job driving trucks for his younger brother’s delivery company, Route 1 LLC. “And that’s big. The program organized so much for me. I went to enroll the day I got my parole, Aug. 27. Maybe a week later, I was enrolled. And I transferred in with a 4.0, so I received the Warrior merit scholarship. To have those things in place was important, and so was me having a great support system with my family. Everything converged at the same time for me.”

Roden noted that he has still faced several hurdles, including a steep lack of technological savvy. Not unlike Byrd and others, he realizes that the digital boom that occurred during his incarceration presented perhaps the biggest gulf between him and more traditional students.

“Coming in, I couldn’t use a computer,” he said. “Even now, I transferred in with a 4.0, and my grades aren’t what they need to be. I had to learn how to use a computer and a phone at the same time, and then I had to learn everything else that was being thrown at me: I had to learn how to get from one place to another, and then learn how to use the phone or learn how to use a computer, and then learn how to use the Canvas system with the computer. And then I had to handle all these other interactions that I’m having.

“What this program does is it makes school doable,” Roden continued. “It makes it so that they can put school into a package that a person can digest. It’s not so many different things at once. You’d be surprised some of the things that people take for granted that they know — that they have the knowledge of — that prisoners don’t. The objective of incarceration is to separate you — separate you from society, separate you from family, friends. And you get separated from everything: technology, information. And when you’ve been separated for that long, you have to take some special steps into reacclimating.”

But even with all the adjustments, Roden said he’s managing well. Along with his job, he’s toting a full load of classes, with a schedule that includes operations/supply chain management, psychology and African American studies courses. He’s also worked with ETC staff to craft a class schedule that would accommodate his job, and with corrections officials to ensure he can juggle all of his responsibilities — even the ones that require long-distance driving.

“My brother schedules our loads, and I take my schedule and itinerary and send it to the parole office to let them know what I’ve got going on,” Roden said. “It takes about 24 hours. They’ll get me a work pass, and I get on the road and we get to what we’re doing. And in Mr. Topps, I have a person who has gone through what I’m experiencing, so he can give me guidance on the educational side. And on the work side, I get to lean on my brother Jason.”

Roden said he plans to earn his degree (“Everybody in my family has a degree, so I’ve always had a desire to finish my education”) and help his brother expand the trucking business.

“It came down to me having to face my challenges, decide what my choices were and then make some changes,” he said. “And that’s what I did while I was in there. That’s obviously what Mr. Topps did; and now, he’s able to give it back to us, to come back in. I’m an example of his good work. Anybody who’s going to look at me and say, ‘Well, Mr. Roden’s doing pretty good for a guy that's on parole’ should know that I’m a product of the people around me. I really am. I’ve got an excellent family, an excellent support system. I’ve got people who love me.”

Inspiration and aspirations

And, as ETC participant Lawrence Dantzler-Bey explained, those in the program want to inspire their loved ones as much as they look to be inspired. Earning their degrees means giving a boost to more than just themselves.

“My family loves the path that I’ve been on since I got out,” said Dantzler-Bey, 56, who served 38 years before his sentence was commuted by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in January. “And I plan to show them what I can accomplish. I want to show them something they’ve never seen before. I’ve been incarcerated since I was 18 years old. I’m not even two weeks out of prison. People would consider me as a throwaway, like you just take the trash out. My thing is to prove everybody wrong. We can do things or reach heights that other people think you can’t. Even in my family, I’m trying to show them, no matter what hand you’ve been dealt, you can make it all your fortune. Your future is in your hands.”

Unlike some other participants, though, Dantzler-Bey’s future at Wayne State has been delayed. An aspiring business marketing major, he enrolled as a student during the winter semester, but because he was released from prison after being given an earlier release date, he lost a chance to apply a $12,000 scholarship he’d earned to his tuition costs. He chose to withdraw from classes and resume in the spring semester.

“I got my student ID and everything,” he said. “I had to drop classes, and they took the scholarship, but I don’t care. I’m still going to take these classes and get a bachelor’s. I don’t care if I have to pay everything out of pocket: I will sacrifice. I will get two jobs. I have goals, and I’m going to see them through.”

Collins pointed out that Dantzler-Bey’s financial situation is not uncommon, noting that the ETC program sticks with them even when they can’t immediately get into classes.

“An ERD, or early release date, is just a potential date,” she said. “The Michigan Department of Corrections is at liberty to change that date for whatever reason. And we’ve found that it has changed in some instances, but for the most part, people come out on their release date or very close to their release date. If they have to decide after that that they have to withdraw, we don’t leave them there. We are with them at least every other week, checking in.

“And the check-in is not just to say, ‘OK, you need to be on campus in the fall or in spring,’” Collins continued. “It is really getting into their lives, meeting their family members. Sometimes the family member is the one who keeps up with us while they’re incarcerated. We still invite them to events. We ask professors on campus to let them just sit in a class, especially if this was a class they had already registered for, just for them to be able to get an idea of what is coming for them. We certainly don’t jump out of their lives until spring — we stay involved.”

Meanwhile, those in the program remain committed to doing their part, even if they’re between classes. Dantzler-Bey said he’s getting caught up on technology, searching for decent jobs and staying in close contact with Topps and Collins ahead of spring enrollment. He’s also steeling himself for contact with a campus community that will be unlike anything he’s experienced — and that means being ready for those who may not be ready for him.

“I understand that some people may be skeptical of us,” he said. “But that’s OK. I deal with it. I’m confident, and I have integrity, and I think that will win people over. But I’m coming to get my education, so it’s really not for me to convince anyone else about who I am. I hope those coming behind me in the program understand that, too. Be confident. Have integrity. And give the world the best that’s in you. This program has given us a chance to show that — and that chance is all I need.”