Dr. Stephen Farrow became a physician to help his neighbors — little did he realize, his work would take him all over the world.

Farrow, an adjunct professor of internal medicine and endocrinology in the Wayne State University School of Medicine, was recently honored for his service with the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Outstanding Service Award for the Promotion of Endocrine Service to the Underserved. The award recognizes past achievements and encourages the recipients’ continued service.

“I was gratified to receive this award and, frankly, a little surprised,” Farrow said. “People from India, South America and Europe, as well as the U.S., have been recognized for impactful work. To be included among this group is a tremendous honor.”

At the School of Medicine, Farrow consults on inpatient service, provides clinical teaching and conducts research on urban populations.

“Many in Detroit suffer from diabetes and other obesity-related disorders,” said Farrow. “According to the CDC, diabetes costs the U.S. about $327 billion per year in care and lost productivity. As a world-class research institution, Wayne State’s medical research efforts are important at the individual and family levels, but they also affect all of society. Improved prevention and management help improve our quality of life and boost our economy.”

Farrow is also executive director for the National Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute in Mississippi and co-chairs the state’s Obesity Taskforce. He works with colleagues across Mississippi to prevent and mitigate diabetes and obesity, while researching a cure. He splits his time between Detroit and the Gulf Coast to address diabetes and obesity-related disorders.

Humble beginnings

Farrow grew up in Detroit and graduated from Cass Technical High School. He and his three brothers were raised by his mother.

“Mom would sometimes hold three different jobs at the same time. It wasn't easy,” Farrow said. “Mom never told us what we should do with our lives, but she emphasized that our family heritage rests on honor, service, integrity and making a positive contribution to society.”

“She was not alone in conveying this message,” Farrow added. “Youth organizations were a vital part of our lives. The Boys and Girls Clubs, scouting, and the church helped us focus on academics as well as sports. Boys Club scholarships even helped fund our education.”

Farrow was impressed by how generous youth leaders were with their time.

“The leaders’ mentorship and guidance were vital to us achieving our chosen careers,” he said. “My endocrinology population health work and research is a meager attempt to pay this generosity forward.”

Farrow’s mother worked several jobs, including one at a hospital, which inspired him to study medicine.

He attended Wayne State, where he received his bachelor’s in 1981. He also participated in the postbaccalaureate medical program and the National Institutes of Health’s Minority Biomedical Research Support Program, and graduated from the School of Medicine in 1985.

Farrow credits Wayne State’s then-chair of endocrinology Professor James Sowers for inspiring him to go into the discipline.

“Urban areas like Detroit, as well as many rural populations, have high rates of diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity. These are difficult and expensive to manage, and their complications can be severe, interfering with success in school, making a living or raising a family,” Farrow said. “Wayne State’s endocrinology faculty demonstrated how clinical and basic research can be fun and fulfilling, while contributing to improved quality of life for the community.”

One endocrinology faculty member was especially impactful on Farrow’s decision to combine clinical care and community research.

“I was surprised to find my home community reluctant to participate in clinical research studies — ‘we don’t want to be guinea pigs,’ was the common refrain,” he said. “My research mentor — and current chair of endocrinology at Wayne State —professor Warren Lockette encouraged me to consider the issue logically, suggesting ‘Perhaps lack of knowledge about research safeguards, rather than the idea of clinical research itself, is the issue.’”

To address this, Farrow established the Community Health and Hypertension Research, Education and Screening Team (CHHREST), whose volunteers included medical faculty, licensed and student-clinicians, and undergraduates from Wayne State, the University of Michigan and other institutions.

The volunteers delivered education and screening and case-finding events at churches and other community venues. In addition to learning how to reduce their health risks, participants learned how regulations protect the autonomy and safety of research volunteers.

Student-athletes played a key role in CHHREST’s success.

“Congregations expect clinicians to be interested in health screening, but having a high-achieving student-athlete check your blood pressure or blood sugar is a unique experience,” Farrow said.

CHHREST’s 200 volunteers helped reach 6,000 people though 20 locations in a single day — with minimal overhead. This caught the interested of the National Institutes of Health, which invited CHHREST to discuss large-scale, low-cost population health promotion at the Pan American Hypertension Initiative conference.

Branching out

Farrow’s work with CHHREST led to a pair of Veterans Affairs (VA) Service Excellence and Diversity awards. He also led the team that won the VA Enterprise Innovation Competition for implementing novel software to accelerate clinicians’ review of VA electronic medical records.

“The software, which is in use at about 30 VAs, collates diverse health data faster than a clinician can. The clinician can then review an electronic chart in a few minutes — a fraction of the usual time — and spend more time with the patient developing strategies to improve their health,” Farrow said.

Farrow’s VA and CHHREST experiences ultimately led to a role as the founding medical director for the VA enterprise Locum Tenens Program.

“We began by selecting sites throughout the Veterans Health Administration to orient our new physician and nurse hires,” he said. “The Tuskegee/Montgomery, Alabama, VA was our first orientation site.”

The program provided vital services throughout the VA, including endocrinology consultation and care to veterans in the Pacific Islands.

“The Pacific region has high diabetes and obesity rates,” Farrow said. “Veterans often must travel to Hawaii or the continental U.S. for some types of care – an inconvenient, expensive proposition.

“Our endocrinologists traveled by plane to clinics in Hawaii, American Samoa and Guam. We later transferred a VA Locum Tenens endocrinologist to permanent employment with the Hawaii VA.”

International work also took Farrow to South America as part of a Fogarty-sponsored team researching the genetics of hypertension in Bolivians of African descent.

“We investigated blood pressure, renal and sweat gland physiology, nutrition, social determinants of health, and genetic factors in Bolivian African Americans,” Farrow said. “We found a lower prevalence of hypertension in our study population, despite greater frequency of a gene subtype found in some African Americans with hypertension.”

His research travels also included studies at Department of Defense sites like the United States Navy Fighter Weapons School and Naval Special Warfare in San Diego.

“Studying how these highly-fit individuals tolerate physically-demanding training and occupations can help explain the physiologic challenges diabetes and hypertension pose for the average person,” Farrow said.

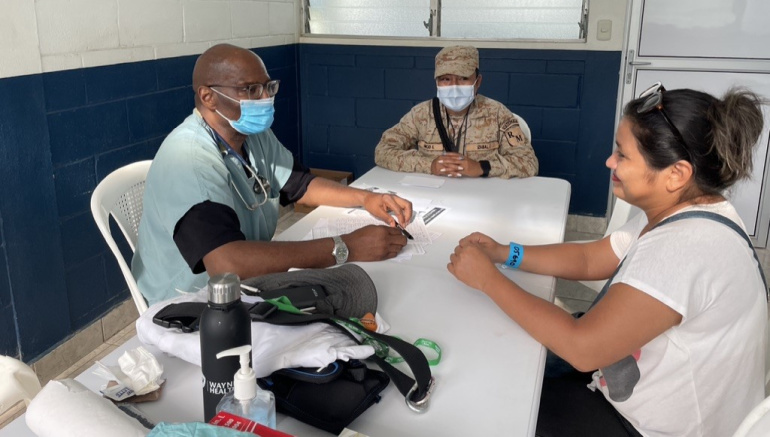

Farrow also supports medical missions. Besides recurring charitable missions to the Philippines with Kiwanis, the Philippine Medical Association, and FANAA, he recently deployed with Wayne State medical colleagues on a medical mission to Guatemala.

Back home

Farrow has travelled the world, but he never lost sight of his hometown. He previously served as a professor at Wayne State for 15 years, but left in 2005 for work in the Gulf Coast and Washington, DC. He returned in his current role in 2022 and said he is delighted to be back with his alma mater to address key urban health problems.

“The best outcomes depend on accurate diagnosis; expert management of behavior, lifestyle, nutrition, and fitness; and appropriate pharmaceuticals. Wayne State has a long and distinguished history of leadership in medical care and research,” Farrow said. “The Detroit Medical Center even has a foundation to help develop and support physician excellence in serving underinsured populations. I am pleased to serve in rounding and clinical teaching capacities to help develop skilled, dedicated clinicians, as we research cardiovascular and metabolic disease in urban Detroit. The road to optimum health is long and complex, but it’s an important, exciting journey.”