Black Bottom was once a thriving neighborhood in Detroit and considered by many to be the city’s epicenter of African American culture. The construction of the Chrysler Freeway in the 1950s leveled the neighborhood, essentially erasing it from the map.

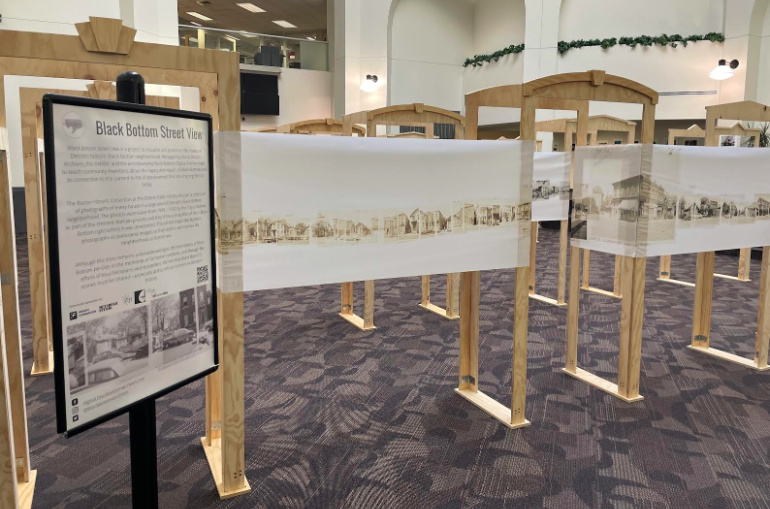

The neighborhood is being brought back to life through the Black Bottom Street View exhibit, which was recently displayed in the David Adamany atrium of Wayne State’s David Adamany Undergraduate Library. Using a series of photos and custom displays, the exhibit creates a panoramic view of Black Bottom that visitors can walk through.

“You can imagine yourself in a neighborhood from a different time, get a sense of what life was like and what the streetscape was like,” said Kevin Deegan-Krause, Ph.D., professor of political science and the Irvin D. Reid Honors College’s foundation sequence curriculum coordinator. “You can see it was a genuine community of people, not necessarily wealthy, but also not the slum that it was made out to be. It’s a real eye-opener.”

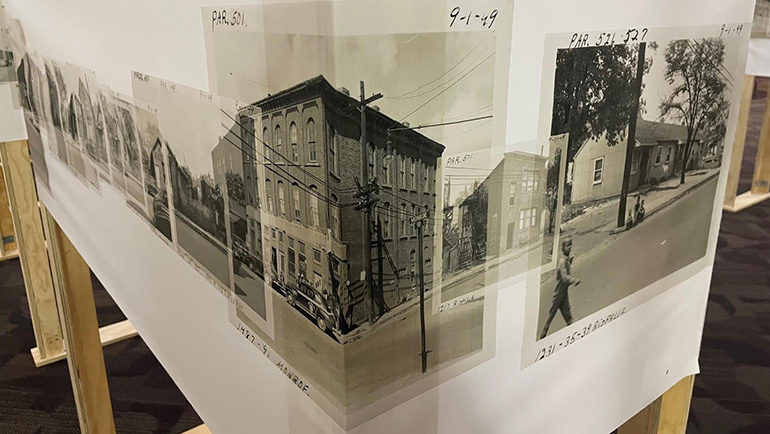

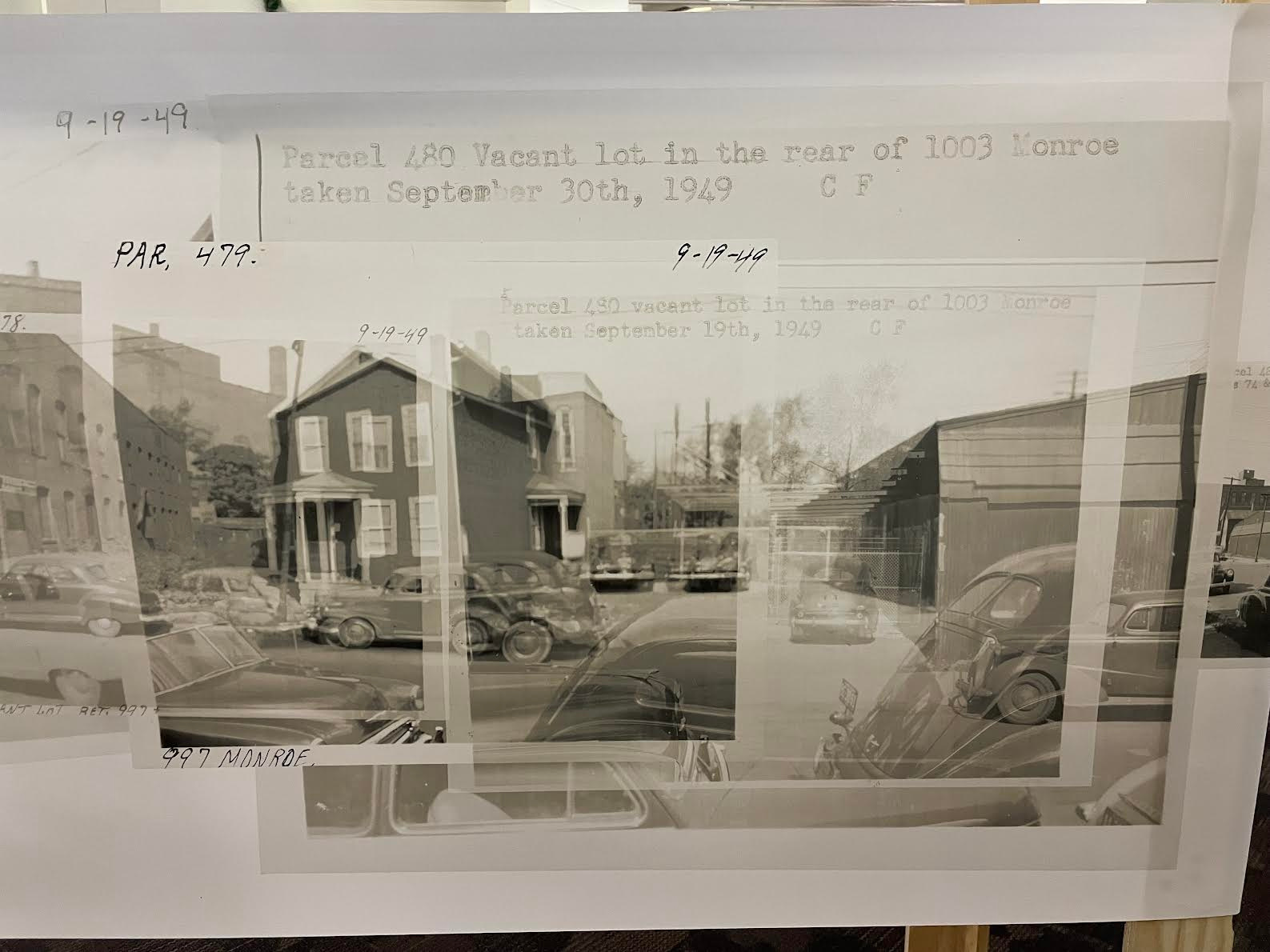

The exhibit was put together by Lawrence Tech professor Emily Kutil, who found a collection of photos of Black Bottom in the Detroit Public Library archives. The city had sent out photographers to shoot every structure in Black Bottom that was set to be demolished as part of the Federal Housing Act of 1949, so the entire neighborhood was documented in nearly 2,000 images.

Kutil used the photos to create something like a Google Street View of Black Bottom.

“The way the exhibit is laid out, recreating the neighborhood is amazing,” Deegan-Krause said. “The design of the exhibit brings people into the space in a way that no amount of individual snapshots could.”

Deegan-Krause played a key role in bringing the exhibit to Wayne State. He teaches about Black Bottom in his Honors 1000 course and has incorporated the exhibit into his class this semester.

“We've looked at various stages of development of the Black Bottom area,” Deegan-Krause said. “The name Black Bottom doesn't come from the people who lived there; it comes from the soil that it was built on. And of course we talk about the demolition of black bottom with the so-called ‘Urban Redevelopment schemes' of the 1950s and 60s.

“It’s important to be aware of the consequences of our actions. One doesn't get the impression that politicians in that time agonized too much over destroying this neighborhood. Yet when it was gone, it was completely gone. We should have a certain amount of respect for the communities around us so that we don't make this kind of mistake again.”

Deegan-Krause said the students enjoy the exhibit and learning about an area that for many people has been lost to time.

“Many of the students never knew Black Bottom existed,” Deegan-Krause said. “They've been to that space, some of them dozens of times, they've driven right through it. And without this kind of exhibit, it's invisible.”

The Black Bottom exhibit is not the only way that the community can experience Detroit history at the UGL. On the second floor of the library is an exhibit featuring the work of renowned architect Albert Kahn. Kahn designed the construction of many of Detroit’s skyscrapers, office buildings, mansions and automotive plants.

“The exhibit is the result of a concerted effort by the Albert Kahn Memorial Foundation to celebrate the life and the works of, arguably, Detroit's most prominent architect and citizens,” Deegan-Krause said. “Albert Kahn revolutionized industrial architecture, and in the process really revolutionized industrial processes in the world in general. The factory world was fundamentally changed by his ability to use reinforced concrete and other techniques to create these large open factory floors that accommodated the new moving assembly line technology.”