At what age did you start taking athletics seriously?

I gradually increased my commitment over high school and, in particular, near the end of high school, as I could see that a college scholarship was possible if I improved my current race times. I got more serious in college. After I graduated, I got very committed, as I sensed I could be successful at distances that were not run in college, such as the marathon. A few years post-college, I started having lots of success in road races, such as 10Ks and half marathons, and I was highly ranked in Canada and decided to attempt to make the Olympics.

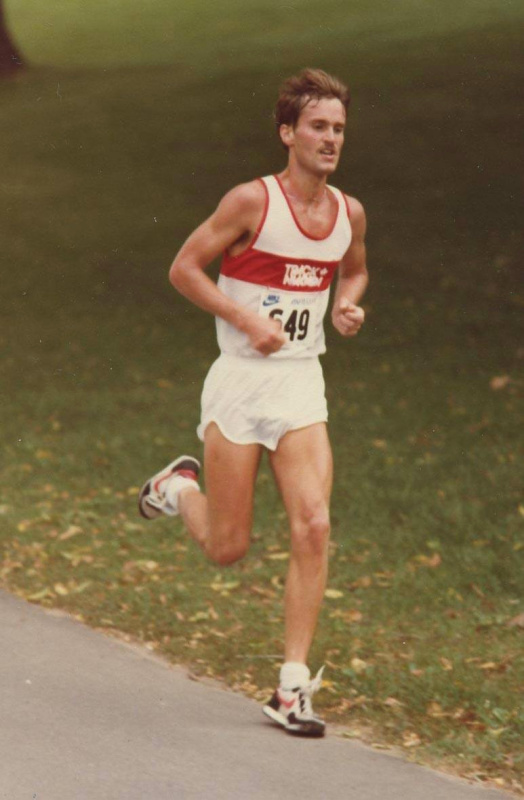

Tell me about your experience in the 1984 Olympics.

I did not make the ‘84 Olympic team, as I finished fifth in the trials race and only the top three run in the Olympics. The trial race was only my third marathon and I was still young — 26 — and decided I would be in my prime in 1988, so I committed to making the 1988 team. The 1984 Olympic trial race qualified me for the five-person team for the 1985 World Championships in Japan and the 1987 World Championships in Korea.

During that time, I won 10 out of 12 marathons around the world in cities such as in Milan, Italy (twice); Barbados; Manila, Philippines; Virginia Beach, Virginia; Charlotte, North Carolina; and a number of top three placings in areas including Bermuda and Toronto.

I loved the travel that came with racing, and would often spend a few weeks in each country I raced in. I decided to retire in 1988 when the Canadian Olympic committee decided to not have a trials race for the 1988 Olympic team but decided to preselect a team based on time, and my times were not fast enough.

When did you become focused on sports psychology?

When I started graduate school. During my running, I had experienced the importance of mental factors for racing and training, so I knew that was what I was interested in for graduate school. I was a psychology undergraduate major and enjoy all sports, so it was a natural fit.

How does sports psychology come into play with Olympic athletes?

Learning mental skills — such as imagery, arousal control, self-talk management and goal setting — are all important for any athlete to reach their potential. But Olympic athletes are often training for four to eight years for that one competition, so they really need to be able to cope with setbacks and challenges over the years through effective mental skills and social support. For the Olympic race, the atmosphere is typically high-pressure and a great deal of stress — especially for first-time Olympians — so knowing how to manage that stress is critical.

Jeffrey Martin is a full professor at Wayne State University. He obtained his Ph. D. in exercise and sport psychology in 1992 from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. His major research agenda has been on the psychosocial aspects of disability sport and physical activity.

Know a Wayne State University faculty or staff member we should spend Five Minutes With? Send along their name, contact information and a few sentences about the person to media@wayne.edu.