In 1963, it was anything but fashionable for self-respecting black militants to publicly disagree with Malcolm X.

The most strident voice of resistance to racial oppression in urban communities in the North, Malcolm X had gained a nearly universal chorus of support from the masses disenchanted with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s unfaltering commitment to nonviolence.

So it took a particularly bold type of university student to — even respectfully — dispute Malcolm X’s fiery oratory when he visited Detroit’s King Solomon Baptist Church in November 1963.

“You haven’t got a revolution that doesn’t involve bloodshed,” he told the audience gathered at the Northern Negro Grass Roots Leadership Conference. “And you’re afraid to bleed.”

Although Malcolm X never called for actual violence, this signature refrain about revolution would usually leave many in the audience silent, giving unspoken assent to his idea about the discomfort created by the rapid change seizing the country at the time.

Not this time, though.

“We’ll bleed, Malcolm!” a group of students shouted back.

“I said you’re afraid to bleed,” Malcolm X repeated.

Again, the activists vociferously begged to differ.

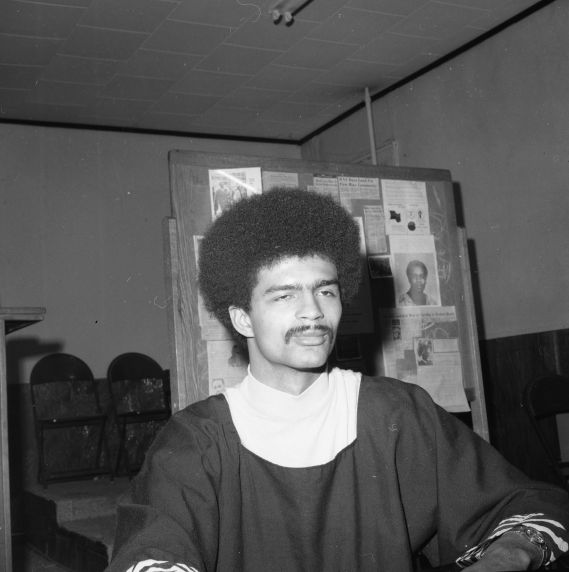

Their sentiments included those of Wayne State University students General Gordon Baker Jr., Charles Simmons, John Watson and others in an organization called UHURU — Swahili for “freedom.” The young crusaders’ presence at what became one of Malcolm X’s most impactful speeches, “Message to the Grass Roots,” wouldn’t be the last time faces from Wayne State gave voice to fearless advocacy for political change.

Indeed, the legacy of progressive black political activism at Wayne State, among both students and faculty, runs long and deep. As both a hotbed for activity and a historical crucible for some of Detroit’s sharpest political minds, Wayne State has had a profound and lasting impact on the political direction of not just Detroit, but black America as a whole.

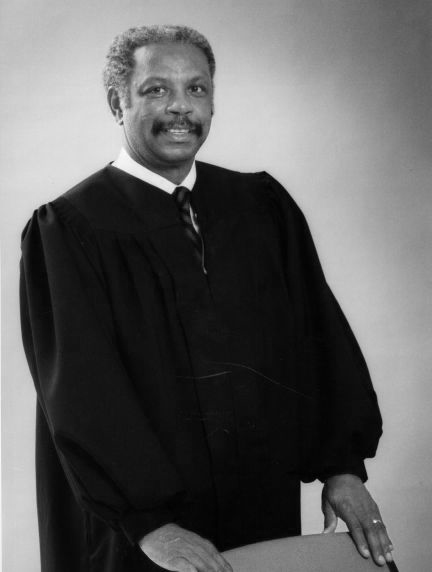

Consider just some of the local progressive icons and influencers to have emerged from the university’s undergraduate and professional programs: venerated former federal judge Damon Keith; former U.S. Congressman John Conyers; the late Detroit City Councilman Ken Cockrel Sr.; activist attorney Chokwe Lumumba; labor organizer General Baker; Black Power theologian Albert Cleage, founder of the Shrine of the Black Madonna; Erma Henderson, the first black woman elected to the Detroit City Council; and Adam Shakoor, social justice lawyer and one-time deputy mayor under Coleman A. Young.

“Look at all the people who came from here, in terms of their lives of struggle,” said David Goldberg, a professor of African American Studies at WSU since 2007. “You have Chokwe Lumumba, you have Ken Cockrel, you have General Baker, and all these people were students at Wayne State University who devoted their lives to being revolutionaries and stayed the course locally.”

Baker, regarded as a pioneer in labor rights, is the subject of Goldberg’s forthcoming biography, tentatively titled Dare to Fight, Dare to Win: The Revolutionary Life of General Baker. According to Goldberg, it was largely within the Wayne State campus environment — against the backdrop of protest movements throughout the ’60s — that Baker developed the consciousness to launch what became the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) with fellow WSU alumni Watson, Cockrel and Luke Tripp.

Now a professor in the social justice graduate program at Marygrove College, Charles Simmons recalled how he, Baker and other UHURU organizers used the Wayne State campus as a mobilization point. Their activism was often informed by real-world experience at Detroit’s manufacturing plants, where Simmons spent several months working before returning to his studies.

“That gave us the education about the labor conditions in the factories, plus our parents and grandparents worked in the factories,” said Simmons.

Goldberg, who discusses the mobilization of black auto workers in 2010’s Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action and the Construction Industry, described the student-influenced LRBW as “the most powerful force of black activism” at the time. He said political maturity was a trait shared by many WSU scholars who strived for racial parity and social transformation.

And with that maturity came a certain boldness. “We were very confrontational, in your face, loud and boisterous,” Simmons said.

With a core of about 20 active members, UHURU demonstrations near Wayne State and throughout the city often drew hundreds, like the group’s 1963 protest outside Detroit police headquarters after a white police officer shot a black woman named Cynthia Scott.

And the students’ influence was felt on campus as well as off.

For instance, at about the same time he helped form LRBW, journalist and UHURU member John Watson took over WSU’s student newspaper, The South End. As LRBW gained influence, Goldberg pointed out, the Black Panther Party was finding footing locally in the wake of the 1967 rebellion.

As a result, a brief merger of the two movements led to regular printings of The South End with a black panther’s emblem on the paper’s masthead.

Rev. V. Lonnie Peek Jr., currently the assistant pastor of Detroit’s Greater Christ Baptist Church, remembers enrolling at WSU in September 1967, just two months after the rebellion. He was almost instantly introduced to the activism electrifying the campus back then.

“My first day on campus … I noticed there were maybe 50 or 60 people outside one building,” Peek remembered. “There was an urban symposium, and they were protesting the lack of community involvement.”

Among the other demonstrators were Frank Joyce and Grace Lee Boggs, wife of Detroit labor activist James Boggs and one of Detroit’s most decorated activists until her death at age 100 in 2015. To Peek’s great surprise, Joyce not only recognized him, but pointed him out when the media asked who represented black students at Wayne State.

“Frank Joyce turned to me and said, ‘He does,’” Peek recalled, chuckling.

When a reporter inquired about Peek’s affiliation, he thought on his feet, citing the not-yet-established Association of Black Students (ABS).

“It was a name I created on the spot,” he said.

The name and the concept not only stuck, but it quickly grew into a force both on campus and in the community. Peek and other ABS members met regularly, recruited new participants and distributed flyers. He ran unchallenged for president of the organization, which set up an office in State Hall, winning support from the dean of Social Work for his efforts. ABS held a symposium that included a two-day workshop examining urban student issues. The group’s ranks swelled to between 200 and 300 under Peek’s leadership in the late 1960s.

“We established ourselves as a viable organization,” he said.

When the organization decided to ask WSU’s administration to create a black studies curriculum, Peek approached President William Rea Keast about resources for a research trip to the West Coast.

“He said, ‘You want me to pay for you to take a trip to California — to go and study programs about black studies?’” Peek said. “I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘You’re a funny man!’”

Keast soon relented, though, and Peek found himself traveling to several universities with a few other ABS members in 1968. They returned to Detroit with what became the eventual blueprint for Wayne State’s original Center for Black Studies.

Thirty-one years later, black WSU students built on ABS’ foundation in two interconnected ways: by demonstrating on campus, and by further advocating for improvements in curriculum, including a full-fledged department that awarded degrees in black social, cultural and political scholarship.

One of those students, Tim Muhammad, recalled how the need to boost diversity even further inspired him to want to take up where Peek and others left off.

“When I got to Wayne State as a theater student, I was pretty shocked,” says Muhammad, a Detroit Denby High grad who recalled how his transition from a predominantly black public school to a mainstream college campus came as “a shock to my sensibility.”

“I was like a fly in a pot of rice,” he remembered.

Wayne State’s still-vibrant political tradition allowed the theater major to find camaraderie with other black students of different academic backgrounds. He remembered the day he first learned about plans for what eventually became an 11-day “study-in” and takeover of campus buildings in 1989 to demand an accredited program that would replace the Center for Black Studies.

“I was walking through Gullen Mall, about to go into the Student Center, when somebody asked if I’d been to the rally,” Muhammad recalled.

He hadn’t even heard about the gathering, but he became active in plans for the study-in from that point forward. Eventually, the student demonstration — in which about 150 students initially occupied four buildings on campus — gave birth in 1990 to the current Department of African American Studies.

“The struggles were brutal,” recalled author and educator Gloria House, Ph.D., a former Wayne State faculty member who advised the students during the study-in.

Previously a faculty member of Wayne State’s Monteith College, House had already amassed an impressive résumé as both an academician and activist by the time of the study-in. A longtime fixture in numerous civil- and human-rights movements in Detroit, House had taught interdisciplinary studies from 1971 to 1998. She also advocated for the hiring of more black professors on campus and instructed a program for inmates at the Jackson State Prison.

At Jackson, she met Ahmad Abdur-Rahman, a former Black Panther convicted to a lengthy prison sentence for a shooting he hadn’t committed. House quickly began to push for his sentence to be commuted. Eventually, in part because of House’s persistence, Abdur-Rahman was freed by the governor in 1992.

Similar legal battles were waged — and often won — by Wayne State Law School graduates Ken Cockrel and Chokwe Lumumba. Frequently called upon as a defense lawyer for Detroit activists, Cockrel had already become something of a celebrity on campus during the ’60s. He accepted high-profile cases that often took on the local political establishment, and helped lead the fight to disband the STRESS (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets) police unit, which had a reputation for racial profiling and abuse. Cockrel won a city council seat in 1977 and was pondering a mayoral campaign when he died in 1989.

Lumumba did become a mayor, being elected to office in Jackson, Mississippi, years after his work as an attorney known for his radical politics and affiliation with Detroit activists including the Republic of New Afrika. A cum laude graduate of Wayne Law, Lumumba went on to represent rap legend Tupac Shakur, and former Black Panthers such as Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, who’d been wrongly convicted of murder. Lumumba, who died in 2014, was highly regarded by many black Jackson residents after bringing many of the same ideals and passions to Mississippi that he’d upheld in Detroit.

The energy and sacrifices made by campus activists haven’t been forgotten.

“The people who started out in UHURU continued throughout most of their lives to engage in social justice wherever they went,” said Simmons.

Similarly, Judge Adam Shakoor and other students of the era later distinguished themselves in community and public service.

Along with Baker, Lumumba and others, names like Gene Cunningham, a former South End editor, and Dan Aldridge are among those Goldberg often mentions when discussing the history activism at WSU.

“It’s been up to black students to advocate for the right to their education and for inclusion of the community,” he said.

Years later, the fruit of that advocacy abounds and is as visible on campus as anywhere else. It is reflected in such strides as the creation of the university’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion, in its deep-rooted commitment to ensuring educational equity for students of color, in rising retention and graduation rates, and in learning communities such as the Warrior Vision and Impact Program and Rise.

Goldberg said present-day challenges like gentrification in the neighborhood surrounding WSU and ongoing concerns about educational equity leave opportunities for activists to assume the mantle of their forebears.

“If the students don’t raise these issues,” he added, “there’s no one to do it.”