When it was announced that part of the Science and Engineering Library would be transformed into the new STEM Innovation Learning Center, it became time to address the elephant in the room.

For 30 years, a fully assembled skeleton of a female Asian elephant named Iki has stood near the library lobby. Behind her bones, a colorful canvas painting depicts her alive, happily grazing in a green grassland among wild birds drinking from an idyllic stream — the kind of place an elephant scholar would love. The kind of place where Dr. Jeheskel Shoshani, Ph.D. ’86, spent his final days exploring and researching his favorite species.

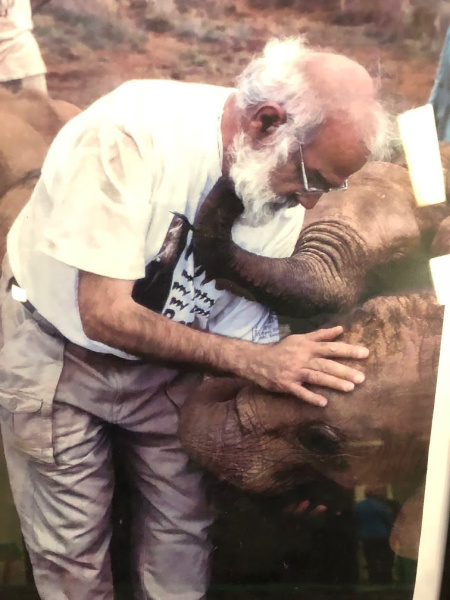

Shoshani was one of the world’s leading elephant experts and spent 25 years teaching at Wayne State University before he was killed when terrorists bombed the bus he was riding in while researching elephants in Ethiopia in 2008. Hezy, as he was called, had been keenly interested in elephants from his youth when he first read a Hebrew copy of Burma Boy while living in Tel Aviv, Israel, and eventually left home to go explore Africa.

His widow, Sandra, says her husband “became fascinated by the description of what elephants could do, for instance, their memory ability, and so when he was in Africa he did a lot of observing of elephants and that’s where the love developed.”

His knowledge of the species became so well known that he was consulted by trivia question writers on the show “Hollywood Squares” and commonly answered elephant questions for national and local news outlets (he was quoted in the Detroit Free Press in 1985 saying that elephants are not, in fact, afraid of mice). Volumes of his research can be found around the world and cited in publications of all kinds, but his most renowned accomplishment at Wayne State was his time leading Project Iki from 1980 until 1988. Though the painting portrays Iki dining in a pachyderm paradise like her Sri Lanka birthplace, the reality was that most of her of 46 years of life were spent as a circus elephant for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. The very same circus that had fielded repeated calls by a persistent professor from Michigan asking if anyone, anywhere had a dead elephant he could have.

In July 1980, the circus called back. The Wayne State representative who took that call informed Sandra, who delivered the news to him while he was working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City for the summer. Overjoyed, Shoshani asked Sandra to gather dissectors on campus and immediately used his own savings to rent a 16,000 pound two-axle Ryder truck that he would take to Florida to fill with 50 blocks of ice and a 3,000 pound dead elephant.

He was ecstatic about the opportunity.

“He had collected a lot of old manuscripts from people who had infected elephants, and there were contradictions about things so he wanted particularly to investigate some of the areas they had questions about and see some of the characteristics himself,” Sandra Shoshani said. “Up until that time, he had only worked in museums but the elephants he handled were basically all skeletons, this was an opportunity to work with organs and tissues.”

Students from Biological Sciences and the School of Medicine joined forces inside a room in the Engineering Building to perform an autopsy on the elephant and remove the tissue from the skeleton, researching and cataloging their findings. Members of the general public, including people with day jobs, were invited to help. Shoshani’s focus was on physiology, and he wanted to measure the amount of water that the stomach could hold. The autopsy concluded in a few short months (Iki had, as the circus concluded, died of natural causes), and the focus on the project until 1988 would be cleaning and preparing the skeleton for display, removing every last bit of tissue and organ.

Bree Schultz Cooper ‘97 was Shoshani’s research assistant from 1996 until his death, and said Project Iki was an engrossingly exciting mystery for the professor to solve.

“Hezy had an incredible ability to connect what looked like disparate pieces of information together to at least postulate more of the story,” Cooper said. “He approached the autopsy with a curiosity about what happened and used that as an educational experience.”

In 1988, Shoshani briefly stopped work on the project and encouraged students to occupy President David Adamany’s office until more funds were released for the project. The university alleged that they had already given funding and could not endorse a blank check on the project, but they eventually gave the remaining funds and the project was completed and installed in the library. Under Shoshani’s direction, students installed the skeleton display, surrounded it with informational signage, and painted the scene behind it. Along with the display, more than a thousand research materials were donated to university’s libraries by Shoshani and other elephant enthusiasts.

The Jeheskel (Hezy) Shoshani Library Endowed Collection (formerly known as the Elephant Research Foundation Library, or ERFL) is a diverse collection of information and display resources about elephants and their relatives, both past and present. The collection of more than 1,100 items continues to grow and exist in other library buildings on campus. It contains published materials, archival material gathered and created by Shoshani during his research, and biological samples. Two of the largest sections of the collection focus on circus and zoo elephants.

Iki’s skeleton is moving to make way for the STEM Innovation Learning Center renovation and will be carefully disassembled, cleaned and restored to her full glory for the building’s grand re-opening in fall 2020. When the new building is finished, Iki will re-emerge.

Ashley Flintoff, director of Planning and Space Management for the university, said that the change will expose more people to Iki by featuring her far more prominently in the new center.

“She’s going to be much more prominently featured, she’s going to be front and center in the middle of the lobby on the first floor. As soon as you walk in the building, you’ll be able to see her from both entrances, and she’s going to be highlighted; this really amazing creature that contributed to so much research and so much knowledge about Asian elephants.”

When completed, the project will transform 100,000 square feet of space into STEM learning facilities. The STEM Innovation Learning Center will include flexible classrooms, seminar spaces, offices and instructional labs that are technology-rich and support hands-on and project-based learning. The center also will have makerhacker labs that offer students interdisciplinary exposure to skill set development that is not possible in most instructional settings.

For now though, it was “until next time.” In September, some of Iki’s fans gathered inside the space where she was displayed for 30 years to host a “Bone Voyage” sendoff. People brought flowers and gifts, ate cake, looked at Wayne State Libraries’ sampling of elephant books, and reminisced about their time with Iki.

Dave Njus, who was then and still is, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, recalled that not even the repugnant odor the elephant spread around the Engineering building in the hot heat of July 1980 could have stopped the determined Shoshani.

“He was an obsessed graduate student really crazy about elephants, he was demanding but also he had a knack for getting people involved,” Njus said, noting that students working on the project went on to practice a variety of professions including dentistry and medicine.

Cooper said Shoshani kept in touch with many students for years after project, and recalled that he had a pride for Wayne State and an uncanny ability to bring others into the project.

“Even through the end of his life he considered Wayne State to be his home institution. His enthusiasm was so infectious and he was so joyful about the material he was interested in and teaching that he would practically bring strangers off the street to help with a project or to explain something, he just had this incredible sense of enthusiasm for the material that he knew and that he was willing to teach. Wanted to share information with anyone who would listen to him for even half a second.

“The elephants were family to him,” Cooper said.

This story originally appeared in the fall 2018 edition of Wayne State Magazine.