The disturbing fact that older adults who live in Detroit are dying at two and a half times the rate of older adults who live in the rest of Michigan will be the topic of discussion at a virtual seminar hosted on Zoom at 6 p.m. Nov. 23 by Herbert Smitherman, M.D., M.P.H, vice dean of Diversity and Community Affairs at the Wayne State University School of Medicine.

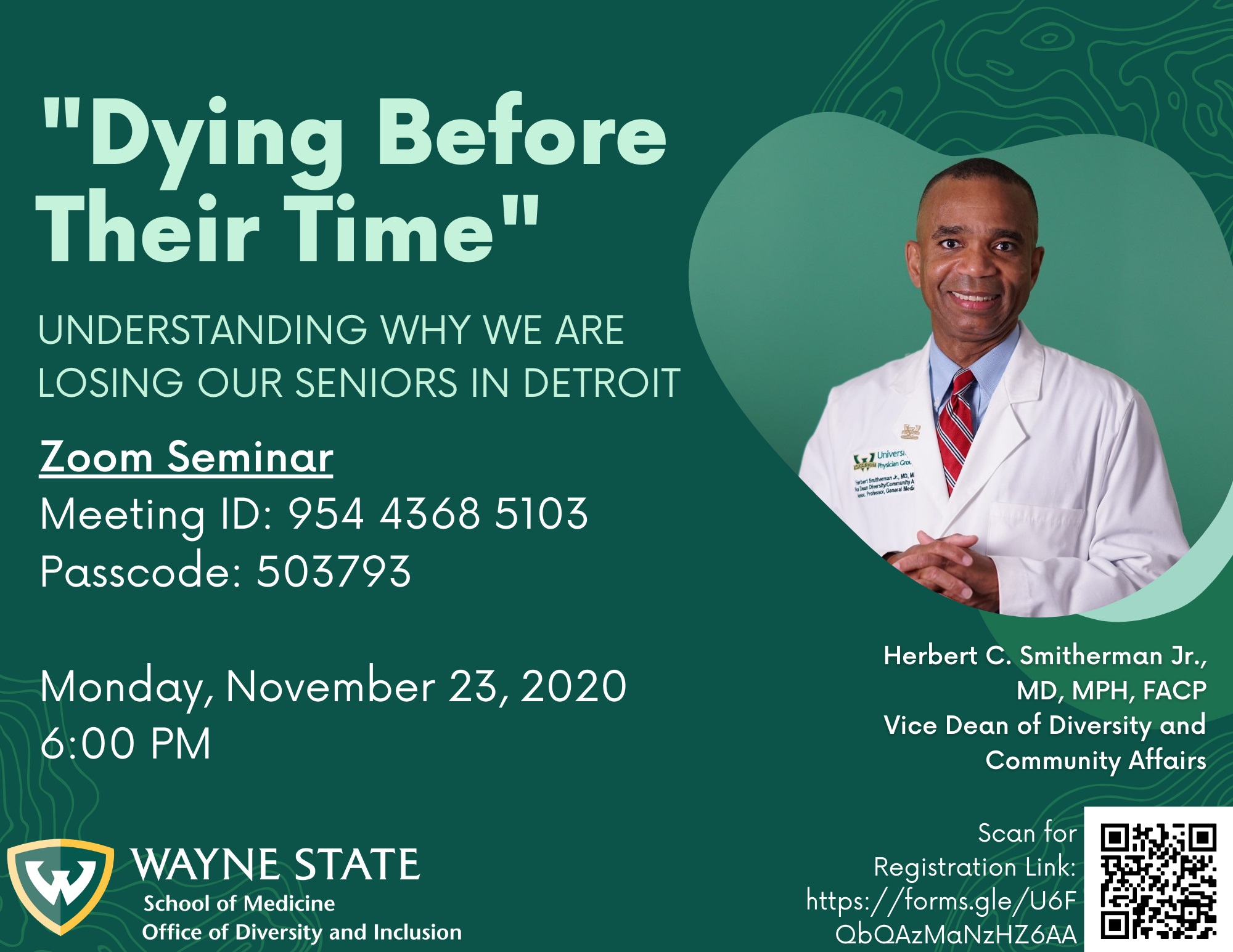

“Dying Before Their Time: Understanding Why We Are Losing Our Seniors in Detroit” shares part of its name with the related report released in August, the latest installment of a longitudinal exploration from 1999 to 2017 launched by WSU researchers when the Detroit Area Agency on Aging noticed the senior population in the city was dwindling.

The seminar will be hosted via Zoom:

Registration: https://forms.gle/4AL3sZ5iyw95KHqM8

Meeting ID: 954 4368 5103

Passcode: 503793

Dr. Smitherman is also president and chief executive officer of Health Centers Detroit Foundation, a Federally Qualified Health Center look-alike in Detroit. His research and expertise focus primarily on creating sustainable systems of care for urban communities. Dr. Smitherman has spent the last two decades working with diverse communities in Detroit to develop urban-based primary-care delivery systems that integrate the health, social goals and concerns of the community. He is the co-author of “Taking Care of the Uninsured: A Path to Reform.”

A week after Dr. Smitherman had lunch with the DAAA’s president and chief executive officer to talk about the issue, the agency commissioned WSU to figure out what was happening to the city’s seniors. The state was blaming migration for the decline. But the DAAA and Dr. Smitherman, a practicing physician and WSU associate professor of Internal Medicine, had a hunch it was something else – something intrinsic to the urban population.

(Read Dr. Smitherman’s op-ed about the report for BridgeDetroit)

“As a physician, I provide medical care. Sixty to 70% of what determines a person’s health status has nothing to do with what I do. Food, clothing, shelter, an appropriate job – these are all issues that determine a person’s health status,” he said.

“When I’m seeing a patient with asthma and CPOD, I write a prescription for a nebulizer and then find out their power is shut off,” he said. “It is not uncommon that I am hip deep in dealing with all these social and economic issues. These are the things I deal with on a daily basis and I just call it urban health care. We need a plan. We need to come together as a country and stop arguing,” he said.

An initial analysis in 2000 found that Detroit lost 23% of its population, with 33% to 36% due to premature death, not out migration. The death rate for 50- to 59-year-olds was 122% higher in Detroit than the rest of the state, and 48% higher than in 60- to 74-year-olds.

“Those excess mortality rates haven’t changed. We’re still losing,” Dr. Smitherman said. “What was happening was almost Darwinian. People weren’t even making it to 60.”

The study is critical to understanding the vulnerability of the older adult population, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, now layered onto a population living with chronic disease.

The solution, he believes, is change.

“You’ve got to have real policy that re-engineers the policies that have gotten us here,” Dr. Smitherman said. “We have the data that show huge disparities of death rates in seniors, and this death rate has been sustained for two decades because we really haven’t had any changes in the current public policy.”

It is a much more deep-seated problem, he added, because health disparities are treated as natural. The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation.

“This is a very fragile and vulnerable population. Now, you pour coronavirus on top. What happens health-wise? It’s like pouring rocket fuel on a fire,” he said. “If you look at racism at the bottom, causing and driving disease epidemic, now you pour coronavirus on it. It’s extraordinarily devastating.

“These are symptoms of racial injustice. What’s driving this is public policy and social determinants of health. These are social and health policy-driven and the reason for all of these disparities,” he added. “Unless we have some public policy changes, we’re going to have this same trend many decades to come.”