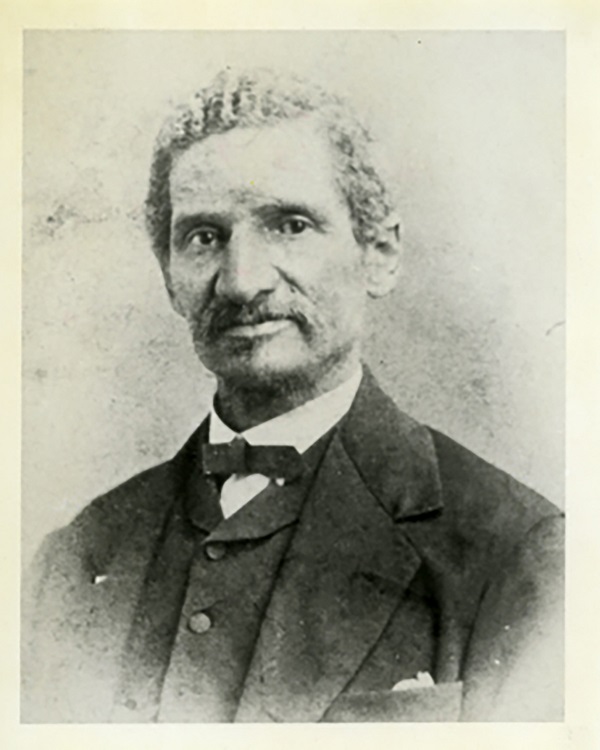

February is Black History Month through the United States. The Wayne State University School of Medicine has a storied history of African Americans of its own that dates back to a mere year after the medical school was founded. Joseph Ferguson, M.D., graduated from what was then Detroit Medical College, in 1869. He became the first Black man in Detroit – and most likely in Michigan – to earn a medical degree.

Fast forward more than 150 years, and the school hit another milestone in 2019 – the 50th anniversary of the Post-Baccalaureate Program, founded in 1969. It was the first of its kind in the nation. Initially launched to address the dearth of Black students entering medical schools, the free program immerses the students into a year-long education in biochemistry, embryology, gross anatomy, histology and physiology. Many who graduated from the program were accepted into the WSU School of Medicine, but the program also served for several years as a major pipeline for Black students into medical schools across the nation. Today, the program accepts economically or educationally disadvantaged first-generation college students who are Michigan residents.

In between, the school continued to play a major role in addressing the physician workforce in America and bridging the gap in health disparities and health outcomes.

The WSU School of Medicine was founded in 1868 by four Civil War veteran physicians. At the same time, the first medical school in the county that was open to all people, Howard University Medical Department, opened in Washington, D.C., under the direction of Civil War veteran and Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, Gen. Oliver Howard. One year later, in 1869, the Detroit College of Medicine and Howard University graduated their first Black physicians.

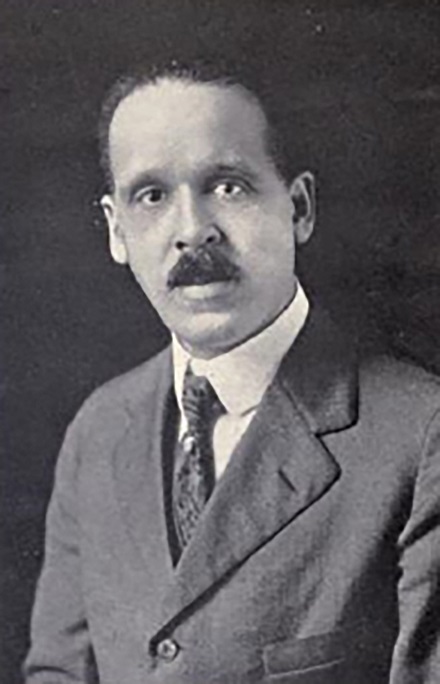

Albert Henry Johnson, M.D., became the third Black graduate of the Detroit College of Medicine, in 1893. Dr. Johnson was one of the founders of Dunbar Hospital, the first Black non-profit hospital in Detroit.

In 1926, Chester Cole Ames, M.D., graduated from the Detroit College of Medicine and Surgery. He was the first Black physician to obtain an internship in Urology at a white hospital in Detroit, but he was never allowed to join staff. Dr. Ames was Detroit's first Black intern, resident and member of the Wayne University medical faculty. He cofounded three Black hospitals in Detroit, but was never granted privileges to practice his specialty in white hospitals.

Some 17 years later, Marjorie Peebles-Meyers, M.D., graduated from the Wayne University College of Medicine, the school’s first Black female graduate. She was also the first Black female resident at Detroit Receiving Hospital, the first Black chief resident at Detroit Receiving Hospital, the first Black female appointed to the WSU medical faculty and the first Black female to join a private white medical practice in Detroit. After retiring, she began a second career as the first Black female medical officer at Ford Motor Co. World Headquarters. Dr. Peebles-Meyers received many awards and honors, including induction into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

The same amount of time elapsed before Black physicians Thomas Flake Sr., M.D., Class of 1951; Addison Prince, M.D.; William Gibson, M.D.; and James Collins, M.D., were appointed to the staff at Harper Hospital, thereby integrating the Detroit Medical Center hospital staff.

Five years later, Charles Whitten, M.D., became the first Black physician to head a department in a Detroit hospital when he was selected clinical director of Pediatrics at Detroit Receiving Hospital. He was also a founder of the aforementioned Post-Baccalaureate Program.

In 1981, Alexa Canady, M.D., became the first Black woman neurosurgeon in the United States. Dr. Canady went on to serve as professor in the WSU Department of Neurosurgery. She was named one of the country’s most outstanding doctors by Child magazine in 2001.

Around 1988, two School of Medicine students – Don Tynes, M.D. ’95, and Carolyn King, M.D. ’93, -- established Reach Out to Youth to introduce children 7 to 11 in underrepresented populations to the possibility of careers in science and medicine. Since then, the hands-on, workshop- and activity-focused program has been presented annually by the School of Medicine’s Black Medical Association, a chapter of the Student National Medical Association.

In 1995, Professor of Pediatrics and Sickle Cell Detection and Information Center Founder Charles Vincent, M.D., was appointed to the Membership Committee of the American Medical Association, making him the first Black doctor appointed to the committee after the AMA was founded 148 years earlier.

In 2017, Cheryl Gibson Fountain, M.D., FACOG, a 1987 graduate, was named the president of the Michigan State Medical Society. The obstetrician/gynecologist served a one-year term as the society’s first Black female president.

Last October, a trio of School of Medicine physicians called upon the medical and scientific communities to confront and end a legacy of scientific racism in research, medical education, clinical practice and health policies by “de-pathologizing and humanizing” American Black bodies. In “Modern Day Drapetomania: Calling Out Scientific Racism,” published in the Journal of General Medicine, the authors – Ijeoma Nnodim Opara, M.D., FAAP, assistant professor of Internal Medicine-Pediatrics; Latonya Riddle-Jones, M.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of Internal Medicine-Pediatrics; and Nakia Allen, M.D., FAAP, clinical associate professor of Pediatrics – note that racism in medicine has “deep historical roots in white supremacy and anti-Blackness, particularly the pathologizing of Black bodies through pseudoscientific claims of the biological significance of the sociopolitical construct that is ‘race,’ which is often incorrectly conflated with ‘genetic ancestry.’”

Today, the push for more diversity, more inclusion and the elimination of health disparities continue to shape the future of the School of Medicine, from student-led efforts to longitudinal research projects dedicated to the health of Black Americans.