Fear of spiders is real, but the historical methods of treating the phobia by bringing actual arachnids into a clinical setting were less than ideal. Now, augmented reality exposure therapy could be the next big thing in the clinical treatment of phobias.

Participants in a pilot parallel randomized controlled trial at the Wayne State University School of Medicine were able to touch a live tarantula or the receptacle containing it after one session of exposure therapy utilizing augmented reality exposure therapy, or ARET. Effects persisted or improved at the one-month follow-up.

Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences Arash Javanbakht, M.D., led the project, in which 25 men and women ages 18 to 45 with arachnophobia were either assigned ARET for arachnophobia, or placed on waitlist control.

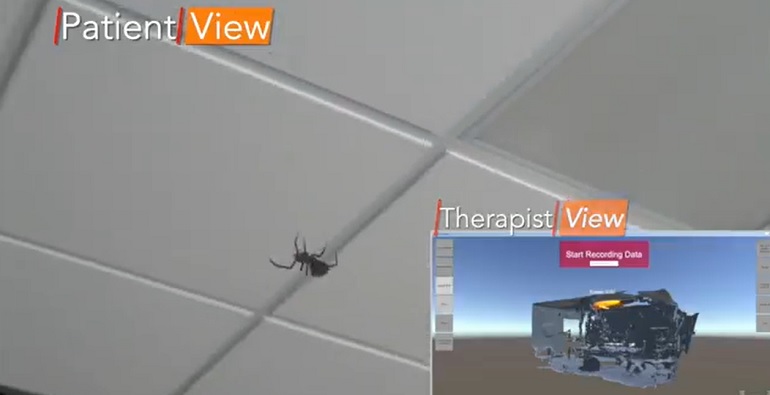

The team, including solutions architect Shantanu Madaboosi, development engineer Rakesh Ramaswamy and doctoral student Lana Ruvolo Grasser, found that ARET can successfully be delivered using the Microsoft HoloLens, a wearable device running novel software with rapid responses and sustained effects. The software connects the clinician’s computer to the AR headset via a local area network, or LAN, providing a three-dimensional visual of the surfaces surrounding the participant. A dropdown menu allows the clinician to choose a hologram and a subtype of the feared object – wolf, jumping or black widow spider – and its color, size, direction of motion and speed.

The detailed results of “Real-life contextualization of exposure therapy using augmented reality: A pilot clinical trial of a novel treatment method,” were published last month in Annals of Clinical Psychiatry.

Participants moved through several levels of exposure in sessions, gradually increasing the speed, proximity and number of augmented spiders crawling on walls and on augmented webs, and changing the setting from an open and airy room to a dark and windowless space.

Replication and expansion of the pilot trial will further support use of ARET for spiders and other specific phobias, such as dogs, snakes and crowds.

Data were collected at baseline, one-week and one-month follow-up, and single-session ARET occurred immediately following baseline collection for the intervention group.

Dr. Javanbakht was initially exposed to augmented reality after watching a TED Talk about the now defunct AR startup Meta that focused on one of the company’s headset prototypes, presented by its Chief Executive Officer Meron Gribetz.

Augmented reality is an interactive human-computer technology that enables mixing virtually-created objects with reality. Instead of creating a completely synthetic environment, AR adds virtually-created objects to the real world. AR only creates the virtual object and not the whole environment, requiring less processing power than VR, and can be less costly.

“I thought it could provide an amazing opportunity for exposure therapy. Exposure therapy is an effective treatment, but its use is limited by lack of access to feared objects – I do not have dogs and spiders in my clinics – and lack of ability to provide it in real-life context. AR can provide access to a wide variety of feared objects, such as dogs of various breeds, sizes and behaviors, fully controlled by the therapist in real-life context. To me this was the ideal solution,” he said. “This all led me to contact the Meta chief executive officer, who was a neuroscientist, and the rest is history.”

That history began in 2016, when Dr. Javanbakht started testing at WSU, in a research setting only, while also working as a clinical psychiatrist. He hasn’t used the AR technology with clinical patients yet, but the University of Nebraska Medical Center is the first clinical site using the technology for treatment of patients outside research setting, he shared.

“Over the next couple months, we will be using the post-traumatic stress disorder product for first-responders to help them overcome their difficulties with being around crowds,” he said.

Dr. Javanbakht focused on the fear of spiders in this initial pilot trial because they are simple enough for a prototype, complicated enough to make sense for the next steps, and other studies from conventional and virtual reality exposure therapy on arachnophobia could be used as a reference point for the study.

“I would like to see it widely used in clinical settings outside the university for treatment of phobias, PTSD and social phobia, as well as training. Also, I would love to see smartphones being used for delivery of the treatment via telemedicine, which will significantly expand the use,” he said.

The treatment does come with its challenges, but raising awareness of the technology could help.

“AR is a very novel technology, and most people are still not even aware of its existence. It is mostly only used in large industrial settings,” he said. “AR programming is not easy and there are not many experts in the area.”

Notably, WSU has selected “Advanced Digital Technologies for Stress, Trauma and Anxiety Research and Treatment (ADT-START),” which focuses on use of the technology, as a Bold Moves priority for philanthropic fundraising.

The project team and a team at Koc University in Istanbul, Turkey, have started the clinical trial for fear of dogs.