When the coronavirus pandemic shifted into full swing in March 2020, most people’s lives changed almost overnight. For two Wayne State University faculty members, their work shifted to a new and urgent focus.

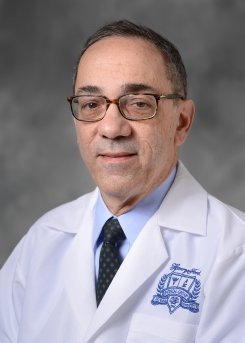

Paul Kilgore, M.P.H., M.D., FACP, associate professor of Pharmacy Practice, and Marcus Zervos, M.D., assistant dean of Global Affairs for the WSU School of Medicine and division head of infectious diseases at Henry Ford Health System, have served as co-principal investigators on the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccine studies in Detroit. Mayur S. Ramesh, M.D., an infectious disease specialist at Henry Ford Health System, was also a co-principal investigator.

The team spent most of 2020 racing to help develop the safe and effective Moderna vaccine, and then turned its attention to what became the Johnson & Johnson single-dose vaccine. Their work has led to the development of two of the three readily available COVID-19 vaccines and has already begun to save lives.

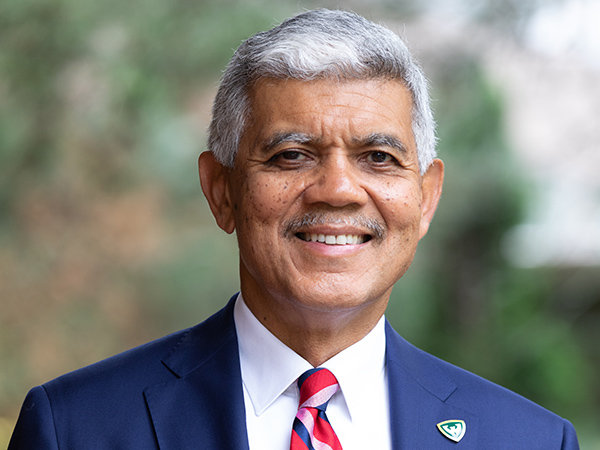

Wayne State University President M. Roy Wilson took a moment to reflect on the work done by Drs. Kilgore and Zervos.

“History will record that the past year was marked by illness, death and uncertainty about the future. But great stories about the human spirit and our capacity to persevere and overcome the odds have begun to emerge from the carnage of the pandemic,” Dr. Wilson said. “The work done by Dr. Kilgore and Dr. Zervos in vaccine development is clearly one of those great stories. Today, their work is saving lives that would have been lost even six months ago.

"This is truly one of the finest examples of Wayne State fulfilling its mission to serve the city of Detroit, the state of Michigan and the entire country,” he continued. “We’ll forever be grateful to Dr. Kilgore and Dr. Zervos for the roles they played in vaccine development and the lasting impact their life-saving work will have on future generations.”

Dr. Kilgore and Dr. Zervos recently sat for an interview about their work and discussed why the process of vaccine development can move more quickly now and how the future of coronaviruses is likely to continue to affect us. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Describe your role in the development of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

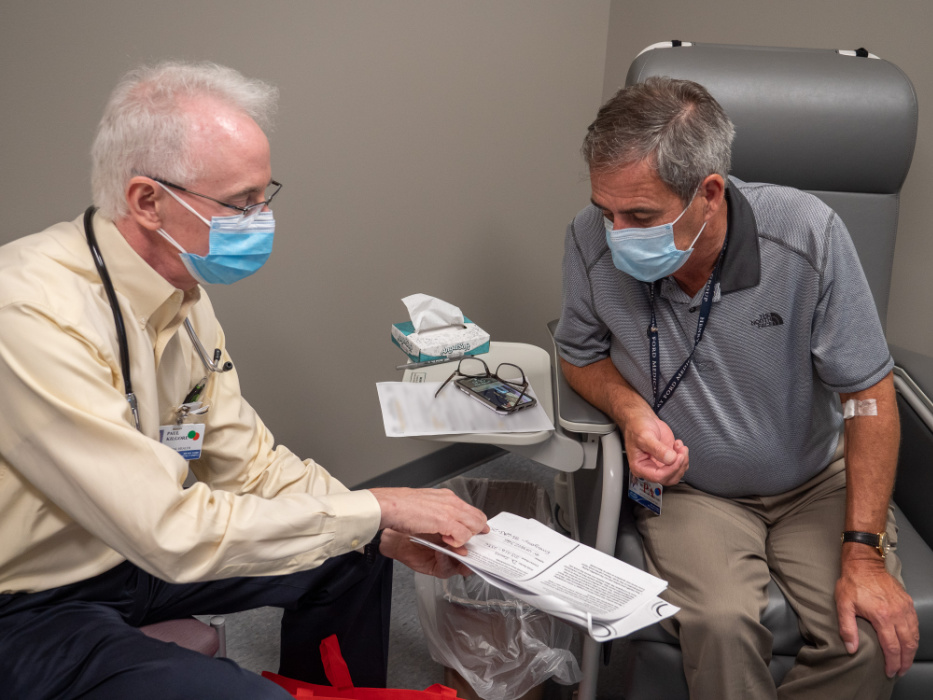

Kilgore: My work in the development of the J&J vaccine has been to co-lead, guide and support our diverse vaccine trial team in Detroit in collaboration with Dr. Zervos. I am responsible for implementation of the vaccine trial that is studying the safety and efficacy of the one-dose J&J vaccine. During enrollment, we conduct a careful informed consent process to make sure all participants know what will happen during the trial. I am also working closely with each of our clinic staff and participants to ensure smooth completion of required procedures and to answer important medical and scientific questions that come from our staff and participants.

Zervos: It is a collaboration between Henry Ford Hospital and Wayne State University. For Moderna, we did the phase 3 double-blind study, resulting in the EUA approval, but for J&J, we were part of three centers in the United States that were a readiness cohort to determine which groups to do the study in. Finally, we conducted two phase 3 trials, the one-dose and two-dose double-blind studies. The one-dose was just recently emergency use authorization (EUA) approved.

How did that work differ from your involvement in the Moderna vaccine?

Kilgore: The vaccine trial protocol for the J&J vaccine has important differences compared with the Moderna vaccine trial. First, we implemented the protocol even as two other vaccines were undergoing and receiving EUA approval. Second, the design of the trial used slightly different criteria for eligibility of participants — we follow these criteria very carefully to make sure we have as diverse a pool of participants as possible. And third, the J&J vaccine is given as a one-dose vaccine in contrast to the Moderna vaccine, which is given as a two-dose series.

Zervos: For both studies, we were among lead enrolling sites and the leading enrolling site of minorities. The J&J study was 168 sites worldwide; Moderna was 89 sites in the United States.

In the past, it typically took four years or longer to develop vaccines for viruses. How can we explain the quick development of this safe and effective vaccine?

Kilgore: Nowadays, we have much better technology and guidelines to develop vaccines than we have had in the past. For example, we can prepare the human study vaccine trial protocols for all phases (1, 2 and 3) from the very beginning. In the past, we would write one protocol (i.e., phase 1) and then wait to see all the results of that trial before preparing the phase 2 protocol. Preparing these complex trial protocols at one time means that we can move more efficiently from phase 1 to 2 to 3 vaccine trials. In addition, in today’s trials, we collect almost all the information during the trial using computers. In the past, we used paper forms, sometimes in triplicate. These forms were cumbersome, could lead to data collection errors and had to be entered from the paper to a computer. Now, with information going directly to the computers, we can easily check and correct any discrepancies in data and then move immediately to the data analysis phase. This means, we can generate results much quicker than in past decades.

Zervos: I would add that we’ve committed a more significant government investment in large numbers of sites to conduct the trial enrollment rapidly, without compromising safety. Moreover, high infection rates in public allowed for efficacy analysis, and manufacturers made vaccine even while the studies were being done to allow for rapid deployment.

Have the variant strains complicated the work of developing an effective vaccine? Does it appear that this vaccine offers protection from the variants?

Kilgore: As scientists, we know that the coronavirus can change often, much like viruses such as influenza or HIV. However, because of the new vaccine design tools we have, creating and adapting the vaccine to new variants is now possible. This also means that we can create new vaccines for the variant strains faster than ever before by using the mRNA and gene-splicing technology to make our vaccines even more effective against new strains.

Zervos: I agree. Johnson & Johnson studied what was going on around the world and included protection against different variants. In addition, there are plans afoot to study booster doses that contain variant activity.

With three vaccines for COVID-19 now widely available, what is your best guess as to how long it will be until we have the pandemic under control?

Kilgore: If we can get 80% of our population vaccinated by the fall of 2021, we will have a good chance of returning to a more normal situation. However, this will depend on all of us pitching in and doing our part to help get everyone who is eligible vaccinated. We are in a race against the variants that are now spreading. Using masks, hand hygiene and distancing can help to reduce spread of the variants. At the same time, making sure we all get vaccinated is a key step toward getting the pandemic under control in the United States.

Zervos: The hope is that by summer we will have enough natural and vaccine immunity to see further drops in cases, but it is important to temper this optimistic outlook by realizing that we probably won’t see total elimination of COVID-19 cases. We are likely to experience more infections and spikes in cases.

Will COVID-19 be a part of our lives moving forward, albeit a manageable problem, much like the flu is today?

Kilgore: Coronaviruses have been around a very long time and even after the pandemic is declared over we will see coronaviruses causing disease. As we evolve our public health response, I believe that one tool in this response will be continued use of vaccines that are adapted to the most common circulating strains of the coronavirus in humans. While it is still too early to tell, we may need an annual or regular booster of coronavirus vaccine to make sure we have good antibody and T-cell immunity against emerging strains that cause serious disease in people.

Zervos: Paul is absolutely correct. We probably won’t ever eradicate coronaviruses, but we’ll cope with them with effective vaccines and better treatment protocols.

Have there been some advantages to having an epidemiologist as president of WSU?

Kilgore: Absolutely. It cannot be overstated how important it is to have leaders who understand the science behind the disease as well as the public health tools that we can use to fight against the disease. President Wilson’s training and experience as an epidemiologist added tremendous value to our campus as we rose to this challenge. This has greatly helped in reducing spread of the illness in the WSU community, and I believe it has saved lives and prevented many illness episodes.

Zervos: No question about it. Having leaders that understand the issues helps to move research forward, a tremendously critical aspect of our battle against this pandemic. Also, President Wilson’s deep commitment to understanding issues of medical disparity clearly guided his decisions in deploying the vaccine to the community.

Kilgore: I am very grateful to the incredible leadership at WSU from the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and the way in which members of the WSU community have worked together, including students, staff, faculty and administration. In this unprecedented experience, being part of a community that works so well together has been extremely rewarding. I also believe the pandemic has brought many together, and this will have great benefits for us all well after the pandemic is brought under control.

Zervos: I hope we have learned lessons from our COVID experience, such as the need to support public health, how best to do the research rapidly, control misinformation, and have consensus and partnerships like we have between the mayor’s office, the Detroit health department, universities and hospitals. This allowed us to do our work and be a model for the rest of the nation. Also, it’s important to note that students had an important role in the testing needed to support how best to deploy vaccines.