As COVID-19 vaccinations continue to roll out across the United States, light appears to be at the end of the tunnel.

But getting everyone inoculated will not happen instantaneously. And with vaccinations being disparately distributed, many who need to receive one might not be able to for at least another six months, possibly longer.

Those are the people the Wayne State University School of Medicine’s James Paxton, M.D., worries about.

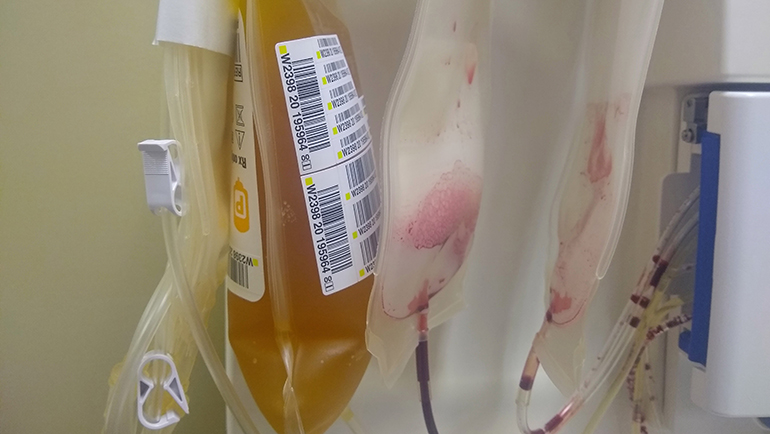

Since last November, Paxton, an assistant professor Emergency Medicine, has been the primary investigator for two outpatient studies of treatments that use blood plasma from people who have had the disease — known as convalescent plasma — to see if antibodies can help fight SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

“Not only do we have to limit the spread of this disease, but we have to be as aggressive as we can in treating it,” Dr. Paxton said. “I think convalescent plasma is one therapeutic option that's going to prove to be effective. We hope it's going to be as safe as it has been in other iterations and with other applications.”

Sponsored through Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, the months-long study aims to recruit at least 1,400 volunteers nationwide. Wayne State is one of 24 participating research entities and the only site in Michigan. Participants will be compensated, and those interested in the plasma trials should visit covidplasmatrial.org or call 888-506-1199.

The first study seeks to use the coronavirus-neutralizing antibodies contained in plasma to protect people who have been recently exposed to COVID-19 but haven't yet become ill, Dr. Paxton said. The second study will use the antibody-filled plasma on recently diagnosed people who have not been admitted to a hospital, in hopes that it will slow or eliminate COVID-19 symptoms.

Dr. Paxton, who also is an emergency physician at DMC Sinai-Grace and Detroit Receiving hospitals, said the study looks to be finished with enrollment by mid-March and will continue to seek participants until then. He said there would be no problem for a person who has received plasma in a study to also receive a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available.

While the vaccine’s efficacy has been shown to be very promising — Pfizer’s touting 95%, for example — “we just don't know how this is going to play out,” Dr. Paxton said. And the plasma antibodies could be effective at reducing COVID-19 symptoms.

“We don't know, for example, how many people are going to be able to enjoy the protection from the vaccine. We need treatments for the 5% of people that the vaccine might not help,” he said. “Unfortunately, many of the studies that have been done to date looking at COVID and studying the effects of interventions have shown either negative results or, in some cases, do harm to the patients.”

That’s why researchers such as Dr. Paxton continue to seek interventions that treat people with COVID-19 who may have gone beyond the point of a vaccine. “Those are the people I think are going to benefit from this type of intervention,” he said.

The concept isn’t new. The medical community has been infusing antibody-containing blood plasma taken from one patient into

another for more than a century, Dr. Paxton said, with similar technology reportedly being used as far back as the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic.

When asked if the vaccine will render convalescent plasma’s role in fighting COVID-19 moot, Paxton prefers to think of it as another component of a physician’s toolkit to help eradicate the virus.

“It's a piece of the puzzle, like the vaccine, but it's for people who have not enjoyed the vaccine’s benefit,” he said. “Maybe it’s a case where it has failed them and they still need to be treated, helped. I think it's going to be a lifesaving intervention for a lot of people who might not have survived without it.

“And while I don't know that we're going to ever get rid of the virus completely,” Dr. Paxton continued, “I think all of us would love to see this become something like the flu that we deal with on a small scale every year — controllable, and not the pandemic we're facing today.”