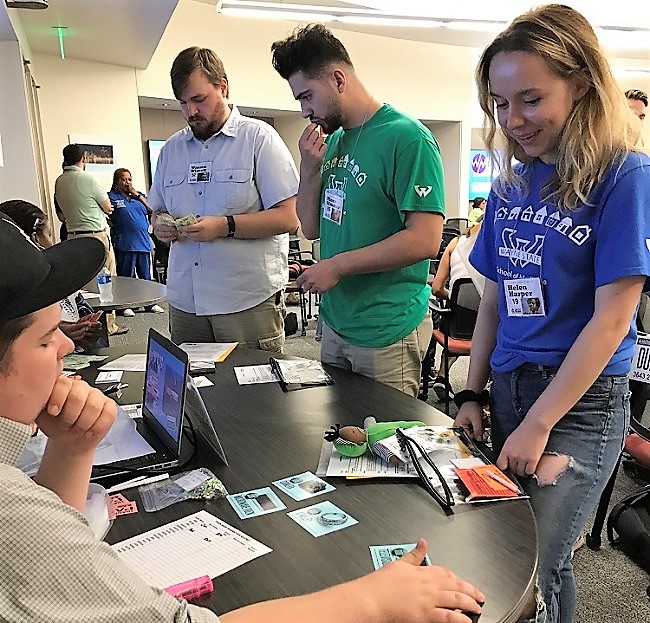

Freshmen medical students tried to "sell" assets like a microwave, and get checks cashed, at a recent Poverty Simulation workshop designed to prepare students for the potential challenges facing their future patients.

"There was pretty much struggle the entire month."

"It was very stressful."

"I definitely felt a sense of hopelessness."

"It is really easy to see how health and education become secondary to basic necessities."

These were the words members of the Wayne State University School of Medicine's Class of 2022 used to explain how they felt to be poor. And while their poverty was simulated, and lasted less than three hours in real time, the experiences they had, shared and witnessed were all rooted in reality.

The school hosted three Poverty Simulation sessions for the nearly 300 freshmen medical students who are taking the required Population, Physician, Patient and Professional course this month. The training provided students with the opportunity to understand what life is like with a shortage of money and an abundance of stress. The goal of the training is to prepare students for the potential challenges facing their future patients, while increasing their empathy and effectiveness as they care for patients facing these daily challenges.

Using a simulation kit, students assumed the roles of families, couples or individuals facing poverty and were required to provide food and shelter. They also had to make decisions on how to spend what little money they were given to survive. Standardized Patients for the School of Medicine played employees representing community resources and services such as a bank, utility company, pawn broker, day care center and more. The students experienced a simulated month -- represented by four 15-minute "weeks" -- and tried to provide for their families while dealing with crime, utility shut-offs, unemployment and a host of other issues.

This year's sessions were hosted by Stacie Smith, M.D., a 2008 graduate of the School of Medicine, and Associate Professor of Pediatrics Nakia Williams, M.D., who teaches the Population, Physician, Patient and Professionalism course. Up to 80 students at a time attended one session each, with the final session held Aug. 16.

"They will be caring for patients in Detroit, where there is over a 60 percent poverty rate. And if you don't know where this patient is coming from, you won't necessarily provide the best care," said Professor of Family Medicine and Public Health Sciences Kendra Schwartz, M.D., M.S.P.H., who taught last year's course.

While that course included more generic locales, "We really tried to make this one Detroit-centric," Dr. Schwartz said.

The students had to visit places like pawn shops, check-cashing stores, banks, social service resources, Detroit hospitals, and even look for work at General Motors Corp.

Detroit native Brandon Foster assumed the identity of an 85-year-old woman with arthritis. "I was really forced to think about it in a greater depth. I felt like it was really eye-opening," he said. "As a future doctor, it makes you more aware. It is difficult getting from point A to point B."

Eventually, Foster, as his character, couldn't afford his medicine because the co-pay was too high. "I had to choose between paying for that and being bedridden," he said.

Like Foster, Dr. Smith grew up in Detroit.

"Growing up, I didn't necessarily experience anything this severe," she said.

But as a teenager volunteering at a local hospital, she watched a patient wince when she was helping him onto a bed and saw a gaping wound on his leg. It bothered her to think that he didn't get treatment sooner. "Consider what's going on with the patient. From that point on, it made me aware, and shaped my view," she said.

School of Medicine students routinely see patients in advanced disease states because of lack of primary or preventive care. What they witness can be amazing from an educational standpoint, she said, but the students should never forget the person with the disease. "Students say, 'I saw such and such pathology. It was cool.' What about the patient?" she asked.

"As doctors, don't judge your patients," Williams told the students. "Learn your community."

To learn more about the training kit, visit http://www.povertysimulation.net/about/