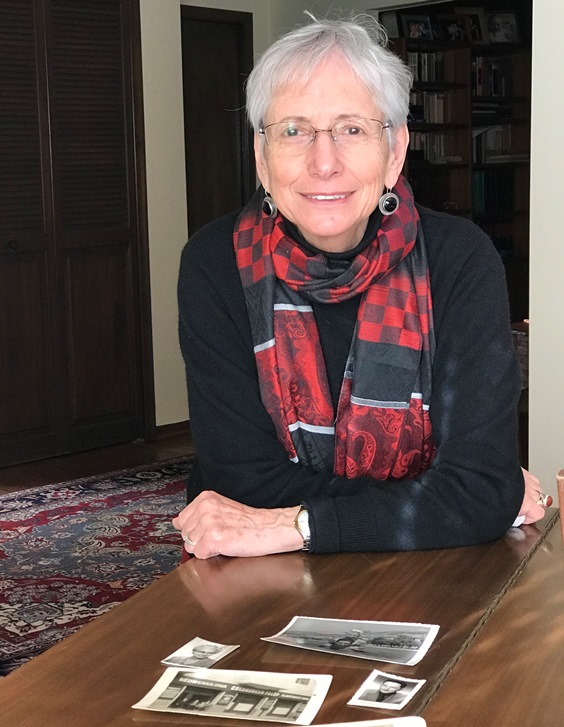

Noemi Ebenstein was 4 years old when she became a refugee.

The Hungary native and Southfield, Mich., resident - interned with her mother and older brother in a World War II Nazi labor/concentration camp in Austria - is a semi-retired clinical psychologist in her 70s who made it her life's work to help people deal with emotional pain, including the ones caused by post-traumatic stress disorder.

Ebenstein was born in 1941 to Jews who believed in education and dignity above all else. She earned her doctorate from the Wayne State University College of Education in 1976.

Dr. Ebenstein also holds a bachelor's degree from Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where she met her husband. In the 1960s, the couple spent five years in the San Francisco bay area, and following completion of her Master's degree in Clinical Psychology, she became interested in group therapy. The couple soon moved to Detroit, and she attend the WSU College of Education where Dr. Mildred Peters, an expert in group dynamics and group therapy, tailored a doctorate program for her, in Guidance and Counseling.

"Above all, I wanted to be a therapist," she said.

One February day in 2017, sitting in her Southfield home, Ebenstein read her copy of The Jewish News. In it was an article about Syrian refugees in southeast Michigan who were interviewed as part of a study at the Wayne State University School of Medicine.

The article showcased preliminary results of "Risk and Resilience in Syrian Refugees," an ongoing study led by Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences Arash Javanbakht, Ph.D. The study measures the impact of violence on Syrian refugee children and their families, specifically the mental health impact and biological correlation of civil war trauma. In all, 30 percent of adult refugees experience post-traumatic stress disorder and 50 percent experience depression. In addition, 60 percent of Syrian children show signs of anxiety because of the trauma - very likely impacted by their mother's PTSD, Dr. Javanbakht said.

The article included a phone number to call to donate to the study.

"I identified with them and I identified with the children. My heart was breaking for these people, so it brought back memories. I was a refugee child," she said. "This article caught my eye because I have worked with people (with PTSD) over the years. PTSD is not that uncommon, and I myself have a little bit of that. It pushed a button for me."

She picked up the phone and made a monetary gift. The School of Medicine is very grateful for the support.

"Noemi's donation is very precious to us, as it comes from deep understanding of the suffering of the refugees," Dr. Javanbakht said. "She is an example of a person with integrity, who has transformed her own pain to a meaningful cause to serve and protect others who suffer. We need more people with this level of empathy and maturity."

After the Allied forces liberated the camp in April 1945, Ebenstein and her mother and brother walked to Bratislava in Czechoslovakia, a distance of two days, since her father was from Subovice, Yugoslavia; the family returned to Sabotica, a border town between Hungary and Yugoslavia. Eventually, Marshall Tito, the president of Yugoslavia, allowed the entire Jewish community of survivors to immigrate legally to Israel in 1948.

Ebenstein said that for her, "the years following the war were years of turbulence." Her parents were imprisoned for their attempt in 1947 to leave the former Yugoslavia and immigrate to Palestine.

"For me, my world fell apart. That was a hard time for me because I was all alone. I was shuffled between relatives for five months until my mother was released. I was only 6," she said. "The message of hope and faith kept my mother going and she instilled that in me. My parents believed in education. When we had nothing, I still had an education."

"The refugees need to hold on to their identity after the basic needs of food and shelter are satisfied. They can reclaim part of that identity. It is important to hold on to your dignity, because then it is easier for you to face the hardships," she said. "I really believe that my story is fairly typical of the Jewish experience in Europe and of all refugees who have war trauma."

She now hopes to volunteer or assist the refugees who are part of the School of Medicine's study.

"To the refugees, I say: believe there will be better times ahead. You go through hell, but you can rise above it, manage your PTSD and have a good life," she said.